Alternative Policing In Action

Ciarán Fitzpatrick, an Éirígí activist currently travelling in Latin America, recently had the privilege of witnessing an exciting social experiment being pioneered by some of the indigenous communities of Mexico. Like the rest of the exploited continent, people in Mexico are beginning to find a sense of their own power in the face of oppressors who are losing influence by the day. Read Ciarán’s account below.

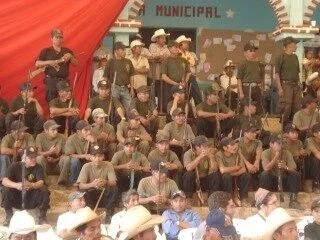

"The 12th anniversary of the Communitarian Police was held on November 16-18 among the community of Zitlaltepec in the state of Guerrero, Mexico.

About 2,000 people, 400 of whom were officers (compañeros), and the Regional Coordinator of Autoridades Comunitarias (CRAC) attended the event. Participating were members of the 53 towns and communities in which the CP operate, alongside these was a mixture of supporters and organisations - various universities, human rights organisations and people like myself with a curious admiration for this radical, social policing initiative.

After an arduous, dusty journey of around six hours on the back of a pickup truck, through some of the most beautiful, yet hazardous mountain landscapes in Mexico we arrived in the village to take part in the celebrations and discussions of this autonomous organisation.

The history of human rights abuses against the people of Guerrero is one of a long list of disgraces that the Mexican government have been responsible for. A zone, which by almost historic tradition has been submerged in marginalisation and poverty but also of struggle and rebellion. The people of Guerrero are stubborn survivors of the dirty war implemented by the federal Mexican government against the guerrilla warfare of Comandante Genaro Vazquez, a Mexican schoolteacher who became a revolutionary, using Emiliano Zapata as his role model.

During the 1990's an intense wave of merciless violence engulfed the mountains and coast of Guerrero. The theft and racist repression against the indigenous communities (Tlapanecas, Mixtecas, Amusgas and Nahuas) perpetrated by various governments has almost been halted by the actions of the Communitarian Police. Within the 53 communities, incidents of rape and robberies have decreased dramatically in the last five years.

The Communitarian Police were created in Guerrero in 1995 not long after the Zapatista uprising in Chiapas and, to some extent, for the same reasons. The people of this municipality (90 per cent of whom are indigenous) like many across Mexico were the targets for what was and still is an almost lawless system where perpetrators of crimes go unpunished by the state authorities. A lot of the time justice amounted to bribing members of the judicial system for lenient or, more often than not, non-existent prison sentences. From 1992 to 1995 the most ruthless wave of violence engulfed the region. Roads were almost impassable with bandits. Robberies, homicides, assaults, cattle rustling, drug trafficking and sexual assaults had reached an all time high.

The state powers did nothing whatsoever to combat these spiralling crime rates and, in many cases, were the actual perpetrators. Then, in late 1995, the crisis became more serious when 39 Aguas Blanca's farmers were massacred by the paramilitary police force.

But, in 1993, the communities affected by these problems of insecurity and violations of their fundamental human rights decided enough was enough and began to schedule meetings to discuss the problems facing their communities with the support of social organisations and the local church. At these assemblies, which were attended by all communitarian authorities, a unanimous decision was taken to uniformly denounce these crimes. At this juncture, a framework was put in place to help the people examine what the best choice would be to try and curtail the out of control crime rates.

Three of the biggest assemblies were held in 1995, the third of which was not attended by any governmental authorities, although they had been invited. The state’s absence demonstrated that they had no interest in resolving the problems of the affected communities and, as a result, the Communitarian Police were established on the principle that they would have to defend themselves against an unjust regime.

The CP is a community organisation whose sole role is to administer justice.

The process of forming the organisation, which was constructed through discussions in local and, later, in regional assemblies, reflects the importance of consensus building and the collective spirit of the communities that are indigenous to the region.

The justice that is imparted by their regional authorities is also based on the communal spirit that is so evident in the region. It is a form of justice that is public and collective and, in many cases, involves the evaluation of those who commit errors within their communities. The most serious conflicts are always resolved under the direction of the assembly; it is the whole community that determines the sanctions, endorsing the actions parallel to the definition of justice set out by the authorities. It is these authorities that are ultimately responsible for administering justice, but, in addition to having the backing of the assembly, they also have the support of the elders' council – the people with a perceived wisdom and respect.

Such forms of organisation have served them as a model by which to construct their regional institution: the Regional Coordinator of Community Authorities. CRAC is the body chosen by the elders, while the Regional Assembly serves to evaluate the most difficult cases so that solutions are collectively achieved.

The main reason for this process is to avoid committing errors or, making arbitrary decisions in the administration of justice.

Given that it was born out of and strengthened by the assembly, the CRAC works alongside the assembly in a parallel manner. The principle directives are: Investigate before prosecuting; reconcile before dictating sentences; re-educate before punishing; don't make distinctions based on age, sex, race, religion or social group; impart a quick and expedited justice.

There weren't any regional assemblies prior to 1995. With the organisation of the security system, a system defined at the regional level originated. Even though the Regional Assemblies deal solely with themes related to security and justice, their operation over the past 12 years represents a great advancement in terms of large-scale co-ordination between communities, spawning a process that is ultimately constructing an autonomous territory where a shared autonomy is being used to deal with territorial control and the administration of justice.

Such a process is enriched precisely by the diversity of the communities and the organisations that come together in the Regional Assembly and is the unique product of the discussions held there. An original product of such discussions is, for example, the norms to apply in administering justice or the steps in the re-education process.

People who are judged by the Regional Coordinator make up for their faults through "social work" which benefits the communities participating in the system.

In accordance with the duration of re-education that is dictated to them, the convicted complete 15 days of work in one community and then are transferred to another. This goes on until they have completed the entire duration of their sentence. In the communities, they are monitored by community police and fed by the community while the general population, particularly the elders, takes on their re-education. This includes speaking with them to make them reflect on their actions. In accordance with this, the process continues until the re-integration of these individuals in society. In this process, the community members also learn to accept those who have fallen and the public presence of the convicted serves as a warning to others the consequences they face should they commit the same errors. It also serves to reinforce a public consciousness that there is a competent authority enforcing fair and effective justice.

Re-education is a new element, which came about in 1998 when they decided to no longer hand over convicts to the Public Ministry. This idea came out of the reflections of various communities from the region about their conflict resolution methods and judicial practices, which have always been in force in their communities. Now, their task is to strengthen the practice of these institutions by using as a yardstick the success these communities have achieved in ensuring the co-existence of justice, peace, security and harmony.

The search for conciliation and justice, which is given freely, and the possibility of speaking in their own languages characterise the new legal system that they, the communities, are formulating. It is a legal system very different from the system that the state imposes upon them and which does not serve to resolve the problems that they as communities must face. It is for these reasons that they felt the necessity to construct a justice and a legal system which reclaim what their communities have done in the past but which also conform to present conditions.

In the construction of their own legal system in the practices of administering and attaining justice and in the processes of communal re-education, they are in fact constructing an autonomous system, which does not depend on the existing institutions for it to function. Despite the fact that state governments have always tried to destroy indigenous organisational and governmental structures, these structures have always remained alive and flourish in their communities. And it is these structures which now give weight, strength and legitimacy to their communal justice and security system.

Cirino Vasquez, a founding member of the CP, and current community representative for the CRAC said, "To defend and to resist today like we have done for 500 years is the aim of the CP. The government says we have no legitimacy. They threaten us, persecute us and even kill us. But we do have legitimacy. The government has law but not the legitimacy. It has force but not legitimacy. We have the right and reason but it depends in our capacity to continue defending what we have little by little."

In my opinion, compañeros and compañeras, this is a perfect example of an alternative to the corrupt and oppressive existence of state policing not just in Mexico but also worldwide even in the so-called "prime nations". Let the people organise themselves for the protection and administration of justice fairly in their communities."