50 Million Euro - But Northern Gaels Have Already Paid A Far Higher Price

On the 20th of February, the Twenty-Six County government announced new funding commitments of over €800 million for ‘Shared Island projects’ which included a €50 million contribution towards the redevelopment of Antrim GAA’s Casement Park in Belfast.

Within days, it became clear that the funding for the redevelopment of this historic stadium would come at a price.

On the 24th of February, just days after that initial announcement, Micheál Martin, the Tánaiste of the Twenty-Six Counties, revealed that the PSNI/RUC was, unsurprisingly, not getting much support from the nationalist community in the Six Counties. Martin then went on to state:

"The GAA can do more there; the GAA should be lock-stop in supporting Catholics going into the PSNI…they should meet with them, engage with them, allow them to brief county boards…and how that its okay to join the PSNI.”

It is clear that Micheál Martin, along with his Fine Gael and Green Party coalition partners, considers certain issues as irrelevant to the affairs of the Twenty-Six County state, issues which still have remain important to people living in the Six Counties.

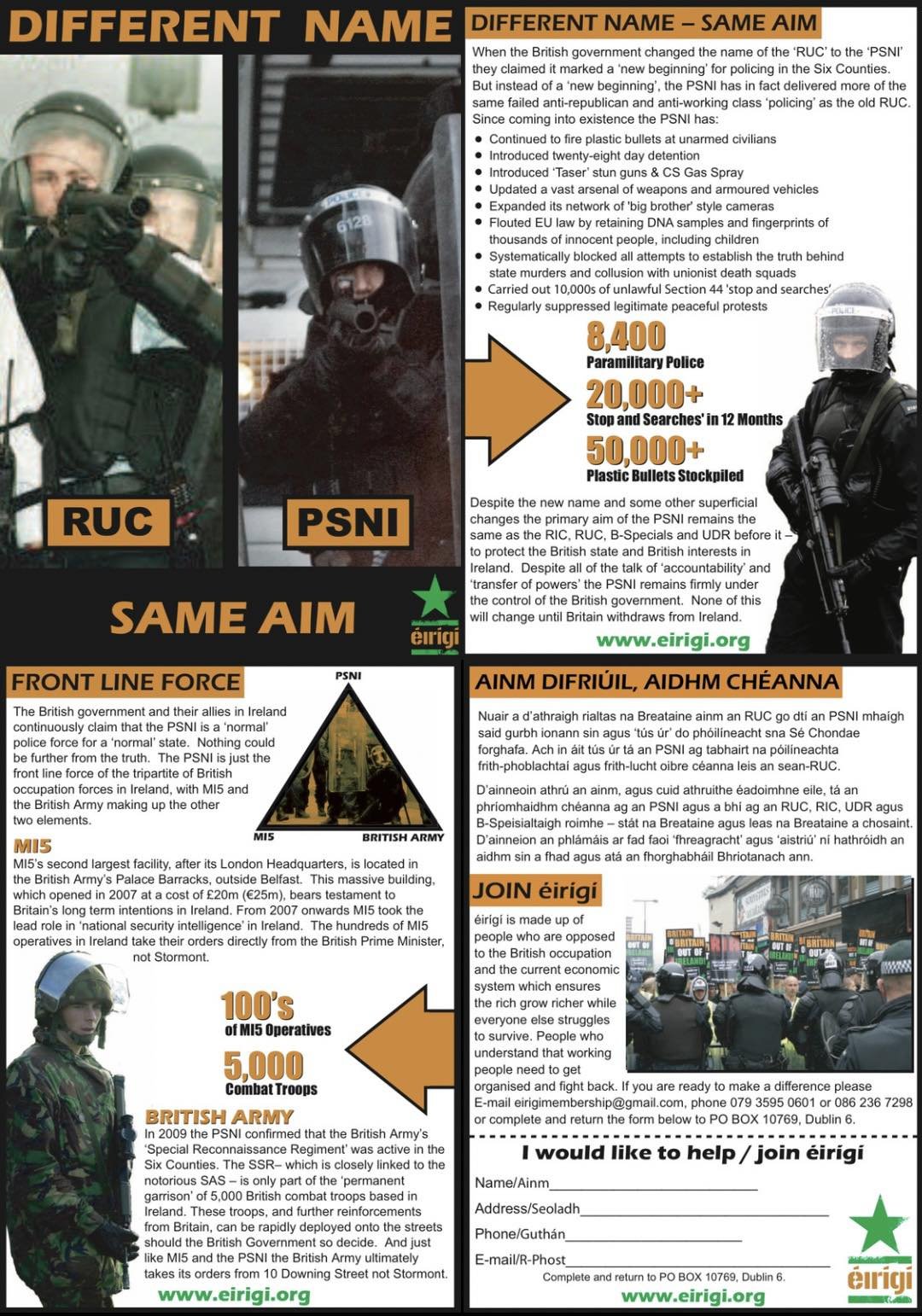

Yes, the RUC has rebranded to the PSNI, but as Éirígí has consistently affirmed about that organisation - Different Name, Same Aim!

Leaflet from our ‘Different Name, Same Aim’ campaign launched in 2009.

Since rebranding in 2001, the PSNI have been responsible for continuously delaying and preventing full investigations into the numerous killings that occurred in the Six Counties in the decades previous, particularly those cases in which there was collusion between the British state and unionist death squads, in addition to killings perpetrated by the state itself.

From 1969 onwards, more than one hundred members of the GAA in the Six Counties were killed by both official and unofficial British forces - the equivalent of almost seven GAA teams.

In 1969, fifteen-year-old Gerard McAuley was shot dead in Belfast as the RUC led unionist mobs in perpetrating pogroms against vulnerable nationalist communities in the city.

In 1971, Martin McShane was murdered on the grounds of Na Fianna GAC in Coalisland, County Tyrone. Sixteen-year-old McShane had been playing with his brothers in the ground when he was shot dead by soldiers of the Royal Marine Commandos who were positioned nearby.

In 1973, thirty-five-year-old farmer Francis McCaughey was murdered in a bomb attack perpetrated by a unionist death squad. McCaughey was a prominent member of his local GAA club in Aughnacloy, County Tyrone. He helped the club to purchase a new playing field shortly before his death. Two years later, in April 1975, the same unionist death squad executed Francis's brother-in-law and club committee member Owen Boyle, a forty-one-year-old father of eight.

In 1975, Sean Farmer and Colm McCartney (a cousin of the poet Seamus Heaney), were murdered by a unionist death squad at a bogus checkpoint set up close to Britain's border in Ireland. The pair had been returning home from watching Derry play Dublin in the all-Ireland semi-final at Croke Park.

In 1981, twenty-year-old Peadar Fagan was shot dead by a unionist death squad in Lurgan, County Armagh - one of his killers was an RUC agent. A member of the Clann Éireann GAC, Fagan was the son of former county captain and Armagh GAA secretary, Gerry Fagan.

In 1988, Aidan McAnespie was shot dead by a British soldier as he walked through a British Army checkpoint at Aughnacloy, County Tyrone on his way to play in a match for his local GAA club.

Naomh Éanna CLG (St Enda’s GAC) in Glengormley, County Antrim has had five of its members killed, along with having its facilities burned down thirteen times during the 1970s and 1980s. In 1993, Sean Fox, a seventy-two-year-old widower and president of St Enda's GAC, was tortured before then being shot dead by a unionist death squad in his own home, located just a few hundred yards from the club.

In 1997, as Sean Brown was locking up the clubhouse of Bellaghy Wolfe Tones GAC in County Derry, of which he was the chairperson, he was approached by members of the unionist death squad who then proceeded to abduct him, dragging him to a waiting car. The car was found burnt out nearly 17 kilometres away. Sean’s body was found beside the car, he had been shot six times. It is now twenty-seven years since Sean’s murder and the PSNI continues to block an inquest into his death.

Nor should Micheál Martin be permitted to forget Volunteer Kevin Lynch from Dungiven in County Derry who was captain of that county's All-Ireland winning under-16 hurling team in 1972. Volunteer Kevin Lynch died on hunger strike in the H-Blocks of Long Kesh in August 1981.

Volunteer Kevin Lynch captaining Derry’s U-16 Hurlers to an All-Ireland title in Croke Park in 1972.

Over the decades, particularly since partition, the GAA as an organisation has sought to steer clear of party politics. In communities across the length and breadth of Ireland the GAA has been a consistent unifying factor for many people with differing political views and opinions. Micheál Martin now wants to reverse that position.

The GAA would be foolish to heed Martin’s call for people from the nationalist community to join the RUC/PSNI; the GAA should instead raise its voice loudly in support of all those families of its members who still are waiting to for the truth and justice they have been denied for decades.

The prospects of success for many families seeking truth and justice have gotten slimmer and more distant with each passing year. Now the British government, acting on behalf of its various agencies, including the RUC/PSNI, intends to scupper the requests of these families for justice by scrapping all existing judicial and investigative mechanisms such as inquests and civil actions through legislation due to come into effect this year.

Serious reservations about this legislation have been raised by a number of international observers, including the Council of Europe's Commissioner for Human Rights and the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights. These are important factors which Micheál Martin neglected to mention in his interview with The Irish News. Perhaps Martin has also forgotten his own government's pledge, made in December, to challenge that legislation through the European Court of Human Rights.

Instead of using the GAA as a literal political football, Micheál Martin should fulfil his own promise to seek justice for those victims of British state and state-sponsored murder.