This sketch of the International Democratic Association is the first in what will be an ongoing series of historically focused articles on the revamped Éirígí For A New Republic website.

In July 1869, Reynolds’s Newspaper reported the foundation of a new association to promote universal liberty, fraternity, and equality. A fierce discussion on its name centred on whether it should be the International Republican Association or the International Democratic Association; the latter won out. A committee was appointed, venues for meetings announced – and a vote of thanks to the chair terminated proceedings.

Two weeks later an address from the IDA appeared in Reynolds’s Newspaper:

“The provisional committee of the International Democratic Association solicit the co-operation of all true Democratic Reformers, Socialists, Republicans, and other proletarians, in their forthcoming battle with ‘the powers that be,’ for the abolition of slavery, the emancipation of the labouring classes from the bondage of oppressive and unremunerative labour, the tyranny of landlords and money lords, the misrule and arbitrary legislation of hereditary usurpers, and the depredations and impositions of an aristocratic clique of soi-disant ‘right honourables’ and purchase-elected (mis) ‘representatives.’ England is ripe for a change, and the sooner it takes place the better.”

A manifesto which, sadly, is as relevant today as it was 150 years ago.

Within weeks of bursting onto the London political scene the IDA held a meeting at Clerkenwell Green, attended by 2,000 people, demanding the immediate unconditional release of Fenian prisoners from their incarceration. They began very much as they intended to carry on.

The IDA had a brief but luminous existence, with much of its activity focussed on two main planks – amnesty for Fenian prisoners, and support for the Paris Commune. Much of the group’s activity was based around regular public meetings in Clerkenwell Green – outside where the Marx Memorial Library now stands – which were frequently attended by large crowds. Large demonstrations were called or supported by the IDA, notably a meeting in Trafalgar Square on 20 September and a monster march attended, Engels said, by about 100,000 people to Hyde Park on 24 October 1869. The IDA was a significant part of a wave of (English) republican protest.

Yet this wave did not break, it carried on throughout 1870 and for much of 1871 holding regular meetings. These were advertised in the Irishman, one of the most radical Irish nationalist papers of the day – the IDA was keen to work with the Irish nationalist currents in London. But the young group attracted the attention of the police; a meeting in May 1870 to rally support for a demonstration in support of French Republicans was reported in The Times as having ‘several police detectives … scattered about the meeting’.

A year later in April 1871 a meeting of a range of republican clubs in London was told of ‘a system of terrorism practised by the police towards the proprietors of houses where Republican meetings had been held. The police paid domiciliary visits to those houses and told the landlords that if they permitted those meetings in future they would lose their licences’. This was a recurring practice; in 1881 police efforts to suppress the formation of a branch of the Land League in Hoxton through similar threats led to questions being asked in Westminster.

The political discourse of the IDA was very much derived from the French Revolutionaries of the 1790s. When they declared their objects and means in ads in the Irishman, universal liberty, equality and fraternity were top of the list, before manhood suffrage, equal constituencies, abolition of the House of Lords and a range of further demands which seem descended from the Chartists. As time went by the reports sent to the Irishman began to refer to the speakers as Citizen rather than Mr – for example in July 1870 ‘At the Bull’s Head, Cross-street, Hatton-gardens, on Sunday last, an able lecture was delivered by Citizen M’Ara, on the obstacles that at present exist in establishing the republic—Citizen Murphy in the chair’. American independence was celebrated on July 4th. The Fenian prisoners were described as ‘immured in our patrician bastilles’ – the influence of France was clear.

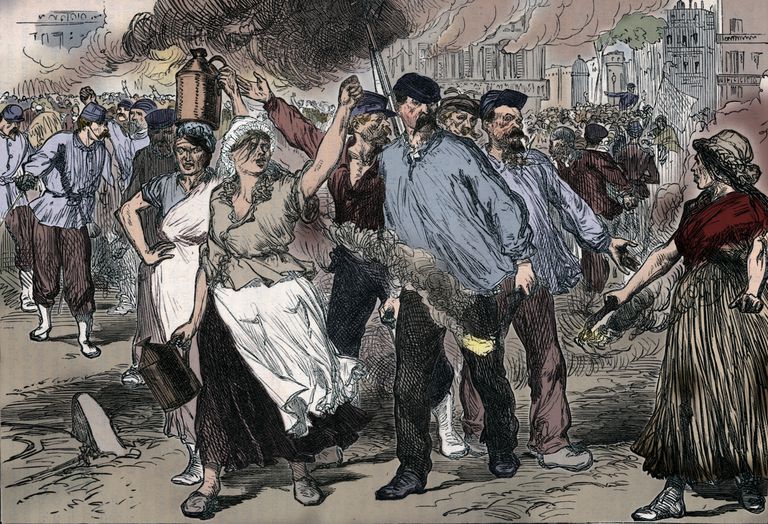

In the Spring of 1871, the IDA championed the Paris Commune, calling a great republican demonstration in April marching from Finsbury Square and Clerkenwell, speeches were given at both the meeting point and at its conclusion in Hyde Park. The Times carried a report of the rather florid fraternal greetings sent to the Communards which ran over wishes for the expropriation of church property, the illegitimacy of the Versailles government, fears of a restoration of the French monarchy and a bitter denunciation of the English press, concluding ‘Long live the Universal Republic, Democratic and Social!” The Times sourly observed the number of foreigners on the demonstration – the idea of ‘outside agitators’ has a long history.

Within months the IDA was no more. In August 1871 it was announced that it was henceforth incorporated into the Universal Republican League; but not before its books were audited and found satisfactory.