All too often the fame of an individual overshadows the remarkable stories and achievements of their family. Such is the case with Jane Wilde, mother of famous playwright and poet, Oscar Wilde.

She was born Jane Francesca Agnes Elgee in 1821, in Wexford. Her family were deeply conservative, and staunchly unionist. Her father died when she was just three, and her mother was left with insufficient funds to provide the type of education to young Jane that would normally have been accessible to someone of her class and social standing.

This lack of formal education did not deter her. She read extensively, having a particular interest in languages – by the time she was 18, she was fluent in ten. However, in spite of her interest in learning – and her family’s deeply held political ideals – politics did not remotely capture her interest. At least, not until she witnessed the funeral of Thomas Davis, a leader of the Young Ireland movement.

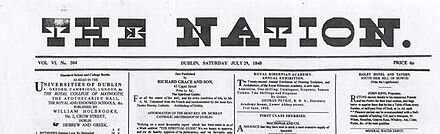

Like Wilde, Davis was a poet – and a Protestant. She began reading his poetry in The Nation, a nationalist paper set up by Davis and two other prominent members of Young Ireland, Charles Gavan Duffy and John Blake Dillon.

The paper was set up when they were part of Daniel O’Connell’s Repeal Association, but all three would break from the Association when Young Ireland shifted from a tendency within O’Connell’s reformist grouping to a standalone revolutionary organisation. Their ideals were centred around an inclusive nationalism, one that ignored ethnic and religious divisions. Despite her unionist background, Jane Wilde was almost immediately taken in by this thinking.

A passionate letter she wrote to The Nation struck a chord with Duffy, the paper’s editor. He recognised the journalistic potential of ‘John Fansworth Ellis’, the pseudonym she chose for her letter. He made contact with Wilde and offered her work. She accepted and, as was the case with all contributors to the paper, she was required to choose a pen name. She chose ‘Speranza’, the Italian word for hope.

At first, she used her knowledge of languages to produce translations of continental revolutionary poems, but she was soon contributing her own poems as well. “Once I had caught the national spirit, all the literature of Irish wrongs and sufferings had an enthralling interest for me,” she declared, “then it was that I discovered that I could write poetry”.

Perhaps the most famous of her poems was The Famine Year, published in 1847, in which she attacked the British political establishment for creating the conditions that allowed famine to ravage rural Ireland, and called the peasantry to revolt:

“Fainting forms, hunger-stricken,

what see you in the offing?

Stately ships to bear our food away,

amid the stranger’s scoffing.”

This call to revolt against British rule was not a once-off, and indeed her writing was often seditious in nature. As Ireland headed towards revolution, she became increasingly outspoken.

Wilde’s unsigned editorial ‘Jacta Alea Est’ (the die is cast), an unmistakable call-to-arms, prompted the suppression of The Nation. The authorities at Dublin Castle shut down the paper and brought the editor to court. Duffy refused to name who had written the offending article. ‘Speranza’ stood up in court and claimed responsibility for the article. The confession was ignored by the authorities – perhaps because of her gender.

In any case, given the large extent to which patriarchal views dominated society at the time, her gender would have been an impediment to her. Indeed, she not only spoke out against British oppression of the Irish people, but was also an early advocate of women’s suffrage, and for women’s rights in the broadest sense.

After the shutting down of The Nation and the failure of the Young Ireland rebellion, Wilde drifted from the nationalist movement. She continued her writing, and eventually settled in London in 1879, where she joined her two sons, Willie and Oscar. Within months, she was contributing wide-ranging articles to various magazines and journals. She also wrote several books, the last of which, Social Studies, contains essays exploring her distinct take on feminism.

It was in London that she passed away in January 1896, at the age of 74, having contracted bronchitis. Oscar paid for her funeral, though a headstone proved too expensive, and she was buried in an unmarked grave in Kensal Green Cemetery.

Fortunately, this was rectified by the Oscar Wilde Society in recent times, who placed a Celtic cross memorial at her resting place. It remembers her as a “writer, translator, poet, nationalist, and early advocate for equality of women”.