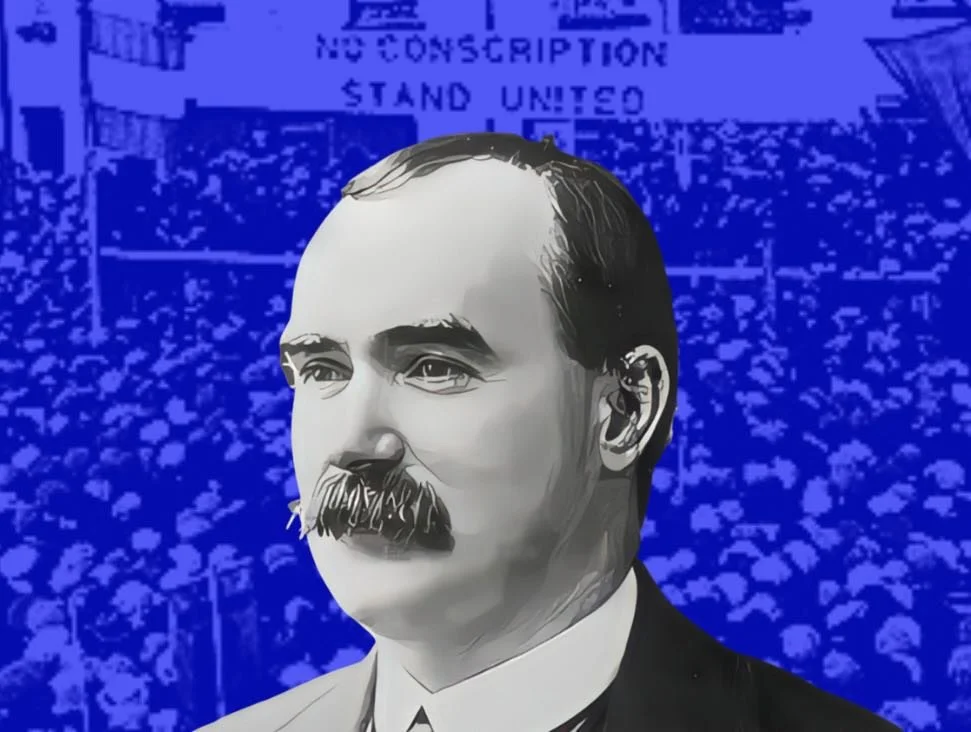

The Connolly Archive - 'Economic Conscription 1'

This month’s addition to the Connolly Archive is ‘Economic Conscription 1’, first published in The Workers’ Republic on the 18th of December 1915.

In this piece, Connolly explores the causes of the weakness of Dublin’s working class population; a weakness which allowed ruthless bosses to leverage their position as the owners of the means of production, in other words the dispensers of much needed resources, to force workers they saw as useless to sign up to fight with the British Army in the First World War.

This was all under the very real threat of starvation and destitution if their employment was withdrawn for refusing to participate in the slaughter.

Recruits for the British Army at the North Wall in Dublin City.

Economic Conscription 1

The Worker’s Republic

18th December, 1915

Of late we have been getting accustomed to this new phrase, economic conscription, or the policy of forcing men into the army by depriving them of the means of earning a livelihood. In Canada it is called hunger-scription. In essence it consists of a recognition of the fact that the working class fight the battles of the rich, that the rich control the jobs or means of existence of the working class, and that therefore if the rich desire to dismiss men eligible for military service they can compel these men to enlist – or starve.

Looking still deeper into the question it is a recognition of the truth that the control of the means of life by private individuals is the root of all tyranny, national, political, militaristic, and that therefore they who control the jobs control the world. Fighting at the front to-day there are many thousands whose whole soul revolts against what they are doing, but who must nevertheless continue fighting and murdering because they were deprived of a living at home, and compelled to enlist that those dear to them may not starve.

Thus under the forms of political freedom the souls of men are subjected to the cruellest tyranny in the world – recruiting has become a great hunting party which the souls and bodies of men as the game to be hunted and trapped.

Every day sees upon the platform the political representatives of the Irish people, busily engaged in destroying the souls, that they might be successful in hunting and capturing the bodies of Irishmen for sale to the English armies.

And every day we feel all around us in the workshop, in the yard, at the docks, in the stables, wherever men are employed, the same economic pressure, the same unyielding relentless force, driving, driving, driving men out from home and home life to fight abroad that the exploiters may rule and rob at home. The downward path to hell is easy once you take the first step.

The first step in the economic conscription of Irishmen was taken when the employers of Dublin locked their workpeople out in 1913 for daring to belong to the Irish Transport and General Workers’ Union. Does that statement astonish you? Well, consider it.

In 1913 the employers of Dublin used the weapons of starvation to try and compel men and women to act against their conscience. In 1915 the employers of Dublin and Ireland in general are employing the weapon of starvation in order to compel men to act against their conscience. The same weapon, the same power derived from the same source.

At the first anti-conscription meeting in the City Hall of Dublin we heard an employer declaim loudly against the iniquity of compelling men to act against their conscience. And yet in 1913 the same employer had been an active spirit in encouraging his fellow-employers to starve a whole countryside in order to compel men and women to act against their conscience.

The great lock-out in 1913-14 was an apprenticeship in brutality – a hardening of the heart of the Irish employing class – whose full acts we are only reaping to-day in the persistent use of the weapon of hunger to compel men to fight for a power they hate, and to abandon a land that they love.

If here and there we find an occasional employer who fought us in 1913 agreeing with our national policy in 1915 it is not because he has become converted, or is ashamed of the unjust use of his powers, but simply that he does not see in economic conscription the profit he fancied he saw in denying to his labourers the right to organise in their own way in 1913.

Do we find fault with the employer for following his own interests? We do not. But neither are we under any illusion as to his motives. In the same manner we take our stand with our own class, nakedly upon our class interests, but believing that these interests are the highest interests of the race.

We cannot conceive of a free Ireland with a subject working class; we cannot conceive of a subject Ireland with a free working class. But we can conceive of a free Ireland with a working class guaranteed the power of freely and peacefully working out its own salvation.

We do not believe that the existence of the British Empire is compatible with either the freedom or security of the Irish working class. That freedom and that security can only come as a result of complete absence of foreign domination. Freedom to control all its own resources is as essential to a community as to an individual.

No individual can develop all his powers if he is even partially under the control of another, even if that other sincerely wishes him well. The powers of the individual can only be developed properly when he has to bear the responsibility of all his own actions, to suffer for his mistakes, and to profit by his achievements.

Man, as man, only arrived at the point at which he is to-day as a result of thousands of years of strivings with nature. In his stumblings forward along the ages he was punished for every mistake. Nature whipped him with cold, with heat, with hunger, with disease, and each whipping helped him to know what to avoid, and what to preserve.

The first great forward step of man was made when he understood the relation between cause and effect – understood that a given action produced and must produce a given result. That no action could possibly be without an effect, that the problem of his life was to find out the causes which produced the effects injurious to him, and having found them out to overcome or make provision against them.

Just as the whippings of nature produced the improvements in the life habits of man, so the whippings naturally following upon social or political errors are the only proper safeguards for the proper development of nationhood.

No nation is worthy of independence until it is independent. No nation is fit to be free until it is free. No man can swim until he has entered the water and failed and been half drowned several times in the attempt to swim.

A free Ireland would make dozens of mistakes, and every mistake would cost it dear, and strengthen it for future efforts. But every time it, by virtue of its own strength, remedied a mistake it would take a long step forward towards security. For security can only come to a nation by a knowledge of some power within itself, some difficulty overcome by a strength which no robber can take away.

What is that of which no robber can deprive us? The answer is, experience. Experience in freedom would strengthen us in power to attain security. Security would strengthen us in our progress towards greater freedom.

Ireland is not the Empire, the Empire is not Ireland. Anything in Ireland that depends upon the Empire depends upon that which the fortunes of war may destroy at any moment, depends upon that which the progress of enlightenment must destroy in the near future. The people of India, of Egypt, cannot be forever enslaved.

Anything in Ireland that depends upon the internal resources of Ireland has a basis and foundation which no disaster to the British Empire can destroy, which disasters to the British Empire may conceivably cause to flourish.

The security of the working class of Ireland then has the same roots as the security of the people of Ireland as a whole. The roots are in Ireland, and can only grow and function properly in an atmosphere of national freedom. And the security of the people of Ireland has the same roots as the security of the Irish working class.

In the closely linked modern world no nation can be free which can nationally connive at the enslavement of any section of that nation. Had the misguided people of Ireland not stood so callously by when the forces of economic conscription were endeavouring to destroy the Irish Transport and General Workers’ Union in 1913, the Irish trade unionists would now be in a better position to fight the economic conscription against Irish nationalists in 1915.

The sympathetic strike with its slogan, ‘an injury to one is the concern of all’, was then the universal object of hatred. It is now recognised that only the sympathetic strike could be powerful enough to save the victims of economic conscription from being forced into the army.

Out of that experience is growing that feeling of identity of interests between the forces of real nationalism and labour which we have long worked and hoped for in Ireland. Labour recognises daily more clearly that its real well-being is linked and bound up with the hope of growth of Irish resources within Ireland, and nationalists realise that the real progress of a nation towards freedom must be measured by the progress of its most subject class.

We want and must have economic conscription in Ireland for Ireland. Not the conscription of men by hunger to compel them to fight for the power that denies them the right to govern their own country, but the conscription by an Irish nation of all the resources of the nation – its land, its railways, its canals, its workshops, its docks, its mines, its mountains, its rivers and streams, its factories and machinery, its horses, its cattle, and its men and women, all co-operating together under one common direction that Ireland may live and bear upon her fruitful bosom the greatest number of the freest people she has ever known.