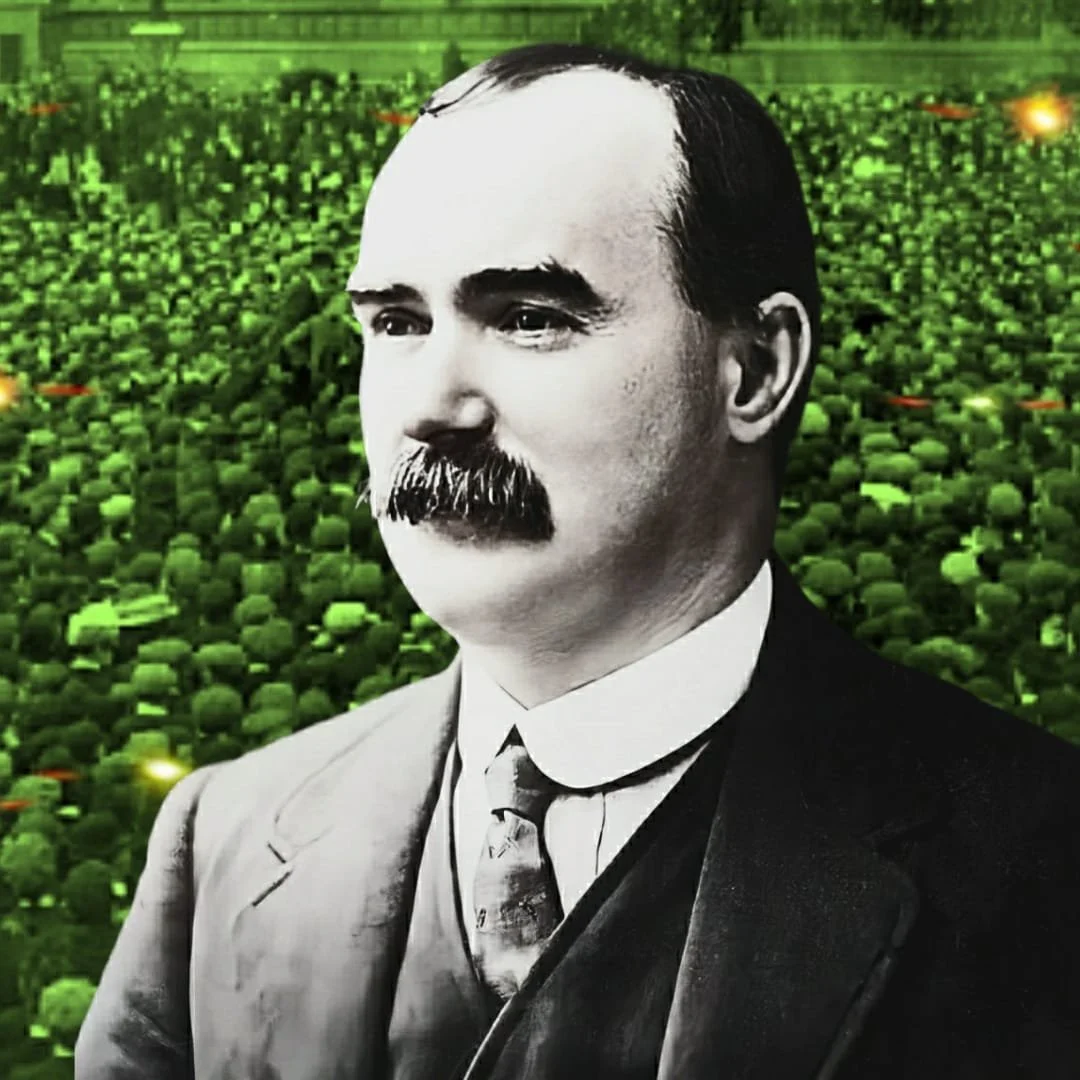

The Connolly Archive - ‘Labour and Politics in Ireland’

This month as part of our Connolly Archive series, we republish ‘Labour and Politics in Ireland’, originally published in The Harp in April 1910. In this piece Connolly identifies contradictions between the effectiveness of labour activists working independently and labour activists working together as a group in striving for meaningful political change.

He gives as an example, the 1899 local election victories of various independent labour candidates from all across Ireland. This came about off the back of a huge turn-out of ordinary workers and farm labourers.

However, the forward momentum of this emerging tendency was curtailed by the lack of political consciousness and collective class identity among the various independents. This proved a major factor in dissuading cooperation between them.

What had the prospects of igniting a national movement was steadily eroded by localised concessions and deal-making between independent Councillors and long established, experienced political parties. The potential of the moment was lost, and the independents were eventually absorbed into the political status quo.

Connolly uses this example to explain as to why the building of a socialist republican party is essential to the successful achievement of real systematic change. If you agree with what he wrote and want to work with like-minded people to build a new all-Ireland Republic of the type that Connolly envisioned, join Éirígí today.

Connolly’s Irish Socialist Republican Party followed in a tradition of Irish revolutionary republican organisations which began with the foundation of the Society of United Irishmen in 1791.

Labour and Politics in Ireland

First published in The Harp, April, 1910

We have not any knowledge of any country in which the working class more readily rallies to an appeal to its class feeling than in Ireland. Whilst the knowledge of theoretical socialism is but meagrely distributed amongst the workers, that feeling or knowledge which the socialists call class consciousness is deep-seated, wide-spread and potent in its influence.

A striking manifestation of this fact was evinced in the action of the trade unions during the first elections under the Local Government Act of 1898. Previous to the passing of this Act the Irish workers had no vote in municipal elections, with the necessary result that local municipal government was completely in the hands of the Irish capitalist class, who kept our Irish cities pest-holes of disease and slovenliness, and made our Irish slums a horror and a byword among the cities of Europe. But in that year the aforementioned Act placed the municipal suffrage upon the same basis as the parliamentary.

Immediately there sprang into existence all throughout Ireland organisations of workers aiming at wresting the municipal government from the hands of the capitalist class, and placing it in the hands of the working class.

Those organisations were formed under the authority of the various Trade Councils and Land and Labour Associations, and were termed Labour Electoral Associations. They selected the constituencies, wards, to be fought solely according to the working class character of these wards, and without regard to the supposed political views of the other candidates. Loyalist and Home Ruler were equal to them; their standard was the standard of labour and under that standard the workers rallied.

To those of us who were privileged to be in the fight in Ireland in those days the manner in which the Irish working class responded to the appeal made to them in 1899 was a promise and a guarantee for the future which no subsequent happenings can ever efface from the memory.

All over the island the candidates of the working class swept to victory – in Dublin, in Cork, in Limerick, down to the smallest agricultural districts, practically every bona-fide labour man showed up well in the balloting, sweeping the old political parties into confusion.

Mr. John Redmond, M.P., begged the Irish workers to show their moderation by electing landlords to the various bodies in Ireland in order to show those gentry that they had nothing to fear from Home Rule. The Irish workers laughed to scorn the whining counsel of this “half-emancipated slave” and stood by the men of their own class, thus ending for ever the jobbing and grafting of the landed gentry at the expense of the rural population. The upheaval of the Irish workers was magnificent

But with victory came demoralisation. We have said that the Irish worker was thoroughly true to his own class, but lacking in socialist knowledge. This alone offers an explanation of the subsequent setback to the labour cause in Ireland.

The men elected all over Ireland had been elected on an independent platform, and all during the election most of them had steadily refused to merge their cause in any other, and had kept their independence intact and unsullied. The splendid vote they received was the emphatic endorsement by the Irish workers of this political independence of labour.

But as soon as they were elected they forgot, or seemed not to realise, this fact, and instead of forming a distinct and independent party of their own in the various councils, they allied themselves to one or other of the factions of the capitalist parties, and became labour tails of the capitalist political kites.

As soon as the shrewd old party politicians saw this they realised immediately that they could regain their lost supremacy. The honest Irish working man – honest himself and inclined to believe in the honesty of others – was no match for the political tricksters of the capitalist parties.

When he found himself flattered and courted, invited to dinners and private gatherings of the Home Rule councillors, plied with drink by his associates and asked to favour them by seconding the resolutions affirming their position on certain debatable matters to come up in the council next day, etc., he did not realise that his genial hosts were destroying his independence, and digging the ground from under him.

Éirígí continues the fight to establish a new all-Ireland Republic of the type envisioned by Connolly.

Yet so it was. The labour party was a party only in name; it came to signify only certain men who could be trusted to draw working class support to the side of certain capitalist factions.

Unfortunately, the only candidate run by the Irish Socialist Republican Party in that year, Mr. E.W. Stewart, the only candidate in the interest of labour who really understood the political trickery of the capitalists, and the manner in which that trickery would manifest itself, and who by his knowledge and pugnacity might have saved the situation, was defeated by a very small majority.

In the years immediately following that first result of the Irish workers on the field of local government the hopeless incapacity to uphold the principle of independent political action in which they had been elected, had its natural result in the overwhelming defeat of every candidate who professed to stand on a labour platform.

The Irish capitalists had learned of the real weakness of the labour movement which had at first so terrified their guilty consciences, and the Irish workers had become disgusted at the poor results shown by the men they had elected.

Though they were perhaps not able to frame it in so many words the Irish workers realised that a working man member of a capitalist party is not necessarily any better than a capitalist member of the same party, perhaps not so good; but that a working man who wishes to safeguard the interests of his class must withdraw from all capitalist political affiliation. And in deciding how he should vote in any great question should consult, not with the capitalist members of the Corporation, but with the committee of the organisations which secured his election.

Now we propose to the toilers of Ireland that it is time to make an effort to retrieve the situation, and once more to raise the banner of a militant Irish labour movement upon the political field. The victories once achieved can be more than duplicated, the mistakes once made will serve as beacons of warning for the guidance of our future activities.

What were the factors at work in 1899? They were: First, a Labour Electoral Association representing an aroused working class in hot rebellion against its social and political outlawry, but ignorant of the real causes of its subjection; second, a small Socialist Republican Party, not much more than two years old, but militant, enthusiastic and with a thorough knowledge of the causes of social and national slavery.

These two factors operated independently – the socialists at all times supporting the labour men, the labour men not always supporting the socialists.

In the nature of things this could not well have been otherwise at that time. But what are the elements in the labour movement in Ireland today? They are a strong socialist movement, representing some of the best intellects in Ireland, an independent socialist feeling and education on socialist thought in every city of industrial activity in Ireland, and a general feeling of comradeship and sympathy between the trade unions and the socialists

The times are ripe for a forward move! We suggest, then, the formation of a political party in Ireland which shall be composed of all bodies organised upon the basis of the principle of labour; that in order to form such a party the Trade and Labour Council of Dublin shall be invited by the socialists to take the lead in calling a conference of labour and socialist organisations of the capital city, that it be set forth in such call that the purpose is to form a party which shall act and be distinct from all others, and entirely guided by the interests of labour.

And in order to secure and maintain the integrity of such party we also suggest that no one should be eligible for office in this party, or eligible to be considered as one of its candidates for any ward or constituency, unless he or she is a member of an affiliated labour union.

When this has been perfected in Dublin then calls should be sent to other Irish cities and towns for the purpose of forming similar bodies; and when a sufficient number have been formed, then a national conference should be called in order to formulate a common programme and concerted action.

The Irish trade unions, the land and labour associations and the socialist party of Ireland could easily find a common ground of action which would leave each free to pursue its ordinary propaganda, to maintain its own separate existence and to serve itself whilst serving others.

Our own hope is to see all Irish economic organisations welded into one great body directing the whole force of labour in Ireland upon any given point at once. But the initiation of our political union need not wait upon the realisation of our economic or industrial union. I t can begin now.

Who will achieve the honour of first moving in that direction? Who will bring this dream of so many minds, this hope of so many souls, to the concrete point of a resolution to test the feelings of the bodies interested?

We have suggested Dublin first, but it is only a suggestion. It is open to any man anywhere who realises that the field of our hopes and destinies in Ireland is lying crying for the hand of the sower to nerve himself to the task.

“England,” said the flamboyant orator of Irish capitalism, “has sown dragon’s teeth and they have sprung up armed men.” Shall we not say that as capitalism has sown poverty, disease and oppression among our Irish race so it will see spring up a crop of working class revolutionists armed with a holy hatred of all its institutions