On The Shoulders Of Giants . . . 'A Thought In The Night' - Bobby Sands

This month, as part of our On The Shoulders of Giants series, and on the 43rd anniversary of the death of INLA Volunteer Mickey Devine - the last 1981 hunger striker to die, we republish ‘A Thought in the Night’, a piece written by Bobby Sands while on the Blanket protest.

Published by ‘Republican News’ in January 1979 under the pen name ‘Marcella’, Sands’ piece depicts an ordinary man who finds himself away from normal life and away from home, confined to a dark, miserable and cold concrete cell - fighting for his life against the combined forces of the prison administration and the British government.

The blanket protest had been going on for over five years by the time Bobby Sands commenced his hunger strike on the 1st of March 1981. In those years the republican prisoners of the H-Blocks and Armagh Gaol fought hard to regain the political status taken away from them five years previously.

Political status, which was first won by hunger-striking republican prisoners in 1972, was cynically withdrawn by the Labour-led British government of the time, meaning that any volunteer sentenced to prison after the 1st of March 1976, was to be treated as nothing more than a common criminal.

This act was the first in a new three pronged strategy concocted by the British government to combat the fight for national liberation. The purpose of this ‘Criminalisation, Ulsterisation and Normalisation’ strategy was to delegitimise the fight for Irish freedom, treating a political act of legitimate resistance as a criminal one - one which would be dealt with locally by the RUC and the UDR.

The resistance of republican prisoners towards this policy became an essential component of the struggle for Irish freedom. Despite these seemingly overwhelming forces, backed up and protected by the might of a British Labour and later a Conservative government, nearly three-hundred and fifty republican prisoners fought against criminalisation for five long years prior to the hunger strike of 1981.

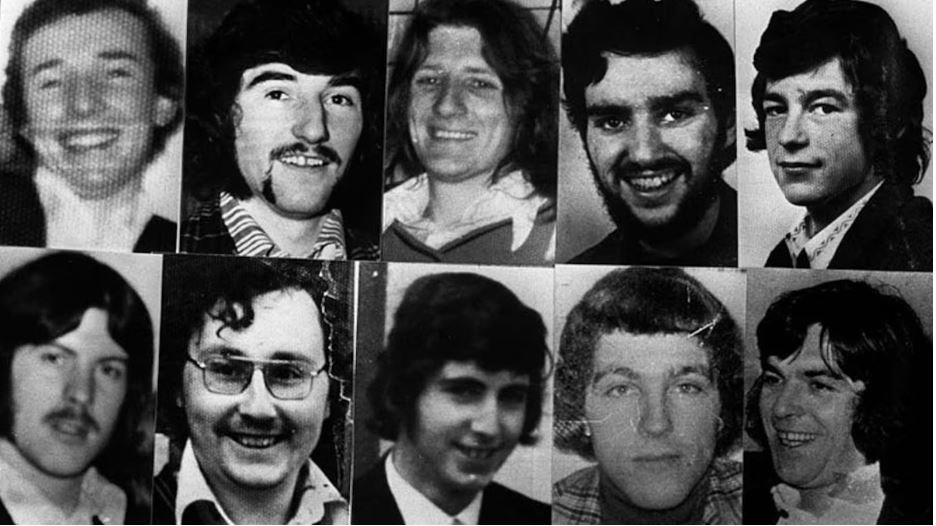

The ten brave patriots who made the ultimate sacrifice in the struggle against the criminalisation of Irish republicanism.

From top left to bottom right: Raymond McCreesh, Kevin Lynch, Bobby Sands, Patsy O’Hara, Thomas McElwee, Kieran Doherty, Mickey Devine, Martin Hurson, Francis Hughes and Joe McDonnell.

A Thought in the Night

by Bobby Sands

First published in ‘Republican News, 6th January , 1979

The wind howled mournfully and swept across the brilliance of a thousand lights illuminating the surrounding sky, while from the outer darkness the heavy rain came hurtling down in sheets of silver crashing upon the black tarmac surface, sending a million fairy-like figures jigging and leaping in a frenzy of movement.

A thousand miles of grey barbed wire wavered and shook in protest as the wind weaved and attacked it relentlessly. An unlocked gate clanged, and the panic- stricken barks of a distant guard dog hugged the wind and were carried into the night. Then, as if the good Lord had snapped his fingers, a silence fell. The wind was tamed and the fairies clung to the grey wire like a multitude of sparkling pearls. The ensuing calm and sudden hush were eerie until disturbed by a moan from the unlocked gate and the sharp piercing cries of the unseen night travellers, the snipe and the curlew. The pools of silver rain glimmered as the passing night settled to recuperate from its raging ordeal and I gazed at a distant star to dream in the newly-born tranquillity, as the cold dampness of the December evening descended.

My thoughts were of my home and family, my wife and son. I tried to visualise the fading faces of my mother and father whom I have not seen for a long time, whom I fear I will not see again. Then came an old companion of mine: depression! It tore at my heart and engulfed me with its unseen shroud of misery. The more I thought of home and family, the deeper I plunged into its darkest depths.

The smile, the soft warm tender smile of my wife, kept coming up out of the darkness in front of me, and I heard her plaintive gentle voice: “I miss you, and I love you, come home.” And my son lay sleeping like an angel, innocent and un- aware of his mother’s hardship and loneliness, with no father to tuck him into bed, to love or emulate as he grew; and he sighed as only an innocent sighs, and rolled over in his dreamy sleep.

Then came the faces of my family, my sisters and brother, growing up in my absence. And I knew just how much I loved them, and how I longed to share this short life with them and my poor mother. Lord, my poor tortured mother, grey and marked with a lifetime of worry and hardship that only she knows the entirety and toll of. And I said: “I’m sorry that you have suffered through my sufferings, mother.” As ever, she replied: “Don’t be humble. You’re my son, and I’ll always stand by you.” My father, quiet as always in his own way, stood beside her. “Take heart, son,” he said, “take heart.”

The sky began to grey as the dawn threatened, and the birds awoke to proclaim the existence of life and nature. In the outer corridor of silence a key jingled and footsteps approached from afar. Depression slipped away unnoticed, as tension attacked my nerves and fear fell with the dawn.

Three hundred and fifty naked bodies stirred, a million thoughts and dreams fled, and a nightmare descended as the sun shone clear. Another day began. The footsteps grew louder and louder, and a voice said: “Get up, you bastards.” I braced myself and thought: “Oh for the darkness of a stormy night.