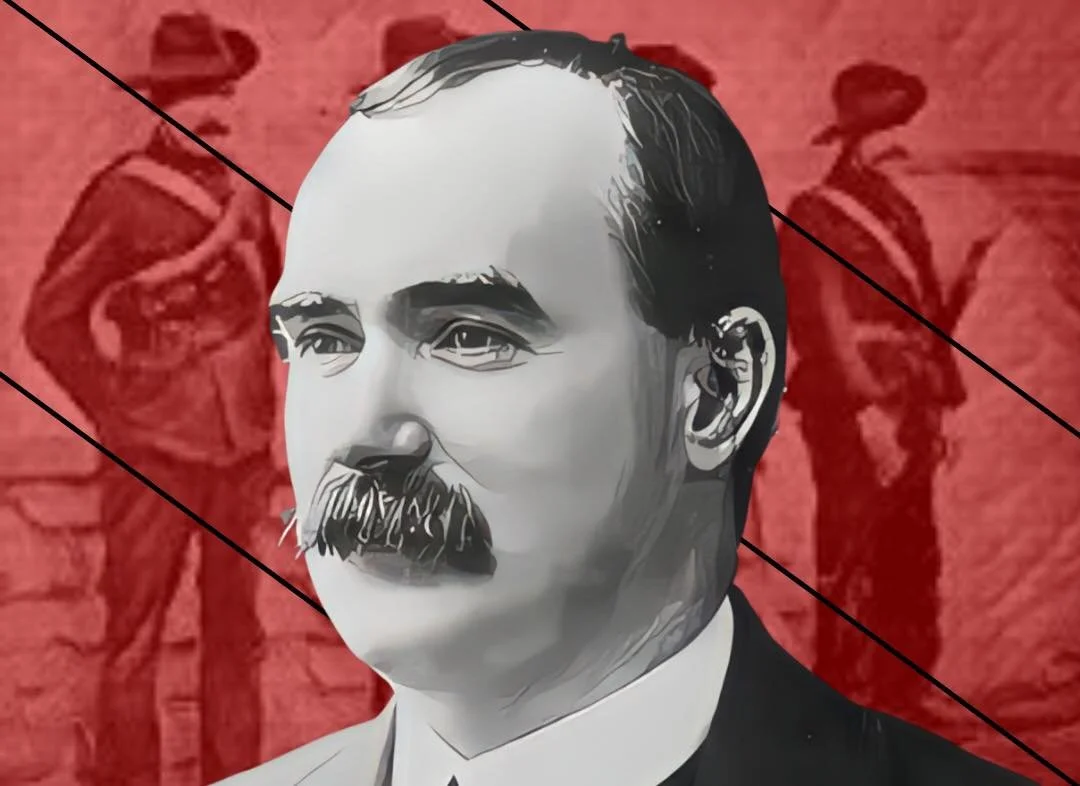

The Connolly Archive - ‘Arms And The Man’

Today we republish “Arms and the Man” as the second instalment of The Connolly Archive. It was first published on this day in 1913 in the Irish Worker newspaper. In the article Connolly writes about The Great Lockout (then ongoing for four months), the foundations of the Irish Citizen Army and the Irish Volunteers (just weeks previously) and the use of armed scab labour by Dublin’s capitalists.

The Irish Citizen Army

Arms and the Man

- ‘Irish Worker’, December 13th, 1913

Somewhere or other we have read that every act brings its own payment; every crime its own punishment. Recent events in Ireland would seem to bear out the truth of that bit of philosophy. We have had on the part of the fervent supporters of the established institutions of the British Empire a continual and increasing fervency of appeal to the arbitrament of force as against the verdict of constitutional government, a rising crescendo of hysterical eloquence invoking the use of arms as against the verdict of votes.

Landlords, ex-Crown lawyers, ax-Ministers of the Crown, aspirants to be Ministers of the Crown, Ministers of the Gospel, smug, sweating capitalists and dear ladies living upon the sweated toll of poor women – all have joined in declaring with one voice that the only course open to lovers of justice and liberty when outvoted is to appeal to the arbitrament of arms, and to bathe with blood the hills and dales of their native land, what time the crack of rifles and zip-zip of machine guns rattled around the banks of our ‘lazy shining rivers.’

The world has looked on amazed, the responsible Ministers of the Crown amused, and the forces of revolution rather pleased than otherwise. But whilst the Government twirled its thumbs rather bored at the spectacle, something was happening in other circles on which the Government had not counted, and which the same Government could not afford, or did not think it could afford, to view with equanimity.

That something took shape and form on the day on which we announced that the Irish Transport & General Workers’ Union proposed to organise and drill a Citizen Army of its own.

At first looked upon as a mere piece of Liberty Hall heroics, it assumed a different aspect when it was discovered that regiments had actually been organised, and drilling under the command of an experienced officer and competent noncommissioned officers was in progress nightly. A parade through the city impressing the onlookers by its discipline and self-control effectually dispelled all illusions as to the deadly earnestness of purpose of the men and their chiefs.

Following this came the uprise of Volunteer forces throughout Nationalist Ireland, and the young stalwart men who have ever cherished high dreams for Erin commenced to learn the rudiments of drill.

And then the Government took action. To allow Orangemen to drill was all right. Their leaders could be trusted to see that no action would be taken which would interfere with the sacred rights of property, or to end the right of the few to rule and rob the many. But to allow Labour to drill and perhaps arm, to allow Nationalists to drill and arm!!! – that would never do!

Hence the Government which allowed the Orange aristocracy to arm and drill the Orange mobs, to supply them with all the implements of war, and to inflame them with the passions of war, promptly and ruthlessly prevented the issue of arms to, or the learning of drill by the people against whom the poor Orange dupes were being armed and excited.

That was instance number one of the manner in which the crime brings its own punishment, the counsel to arm on behalf of the Orange aristocracy bringing inevitably with it the counsel to arm the masses of the Nationalist democracy.

The second instance is of a more tragic as well as of a more – striking nature. During the progress of the present dispute we have seen imported into Dublin some of the lowest elements from the very dregs of the criminal population of Great Britain and Ireland.

This scum of the underworld have come here excited by appeals to the vilest instincts of their natures; these appeals being framed and made by the gentlemen employers of Dublin. They have been incited to betray their fellows fighting against the imposition of an agreement denounced by the highest Court of Inquiry, as well as by public opinion in general, as an interference with individual liberty.

And in order to induce them to act as Judases their rascally passions were pandered to by the offer of wages higher than were ever paid to union men, and by the permission and encouragement to carry murderous weapons.

Too much stress cannot be laid upon this latter encouragement. There are natures so low that permission to carry about the means whereby life may be destroyed has to them an irresistible appeal; the feeling that they carry in their pockets the possibility of destroying others, has to these base natures an intoxication all its own. To that feeling the employers of Dublin deliberately appealed.

Deliberately, and with malice aforethought, they armed a gang of the lowest scoundrels in these islands, and after daily inflaming them with drink, sent them to and fro in the streets of the capital, inciting and maddening all those upon whose liberties they were helping to make war.

In one of the streets on Thursday afternoon, this cold-blooded policy of incitement to outrage had its effect. A few men jeered at the passing scabs and made a show of hostility. Immediately a scab drew a revolver, fired – and shot one of the employers principally responsible for bringing him here and principally responsible for arming him and setting him loose primed with drink upon the streets of Dublin.

That action of the employer in importing and arming such a scoundrel was a crime – an anti-social crime of the foulest nature – and surely never more dramatically did a crime bring its own punishment. It came like a judgment from on high, and what wonder if such was the first thought of the workers when the news was told!

So it will ever be; no act can escape its consequences. And now let us ask if this fearful example will be lost, or will it not help to arouse all to a sense of the fearful dangers incident to the present warfare upon the liberties of the working class of Dublin?

Is it not time that saner counsels prevailed and that now, having fought our battle, tried each other’s mettle and felt each other’s strength, we should sit down to devise means to terminate the present conflict and provide for the possibility of peaceful cooperation replacing the reign of chaos and disorder?