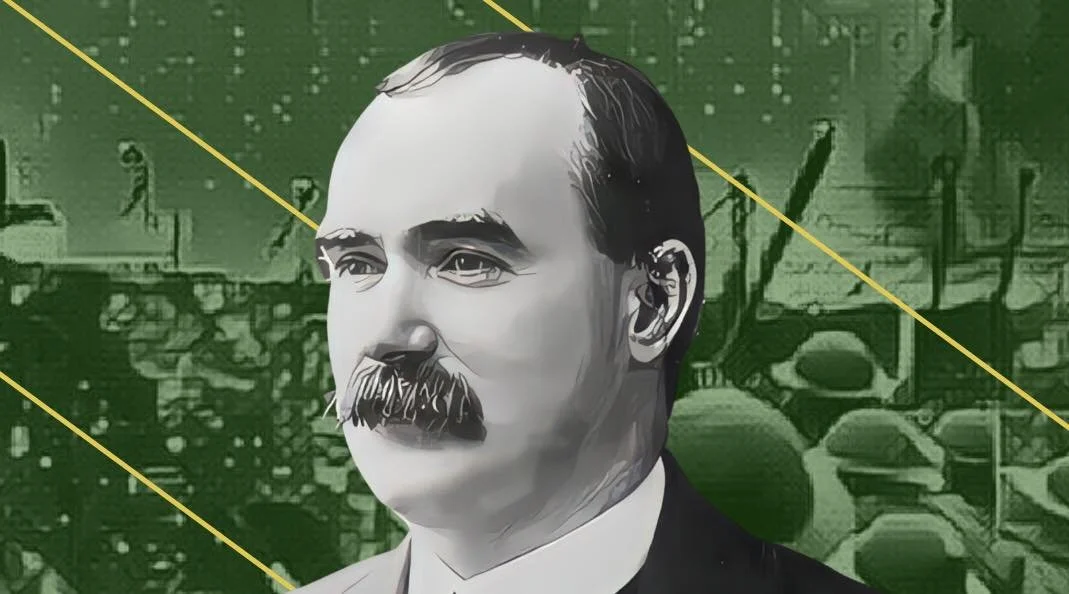

The Connolly Archive - The Slums And The Trenches

Today, as part of our Connolly Archive series, we republish ‘The Slums and the Trenches’, first published in The Workers’ Republic on 26th February 1916.

Connolly insisted that a death in the slums of Dublin was a far more honourable thing than the death of a deluded fool fighting for the British Empire at the behest of the class that persecutes workers.

“Are these poor deluded fools remembered or honoured today? Where in all Ireland could a popular demonstration be organised in their honour. Not in any one part of Ireland would any body of Irish men or women spontaneously turn out to do tribute to their memory.”

James Connolly

The Slums and the Trenches

The Workers’ Republic

26th February 1916

A speaker at a recent recruiting meeting in Dublin declared that the Dublin slums were more unhealthy than the trenches in Flanders, and the same ‘bright saying’ has been repeated in a circular issued by the recruiting authorities.

It is the English idea of wit. Consider it, my friends, consider it well. The trenches in Flanders have been the graves of scores of thousands of young Irishmen, scores of thousands of the physically strongest of the Irish race have met their death there in desperate battle with a brave enemy who bore them no malice and only wished well for their country.

A very large proportion of these young Irishmen were born and reared in the slums and tenement houses of Dublin. These same slums are notorious the world over for their disease-breeding unhealthy character. All the world over it is known that the poor of Dublin are housed under conditions worse than those of any civilised people on God’s earth.

From out of those slums these poor misguided brothers of ours have been tricked and deluded into giving battle for England – into waging war upon the German nation which does not permit anywhere within its boundaries such slums and fever dens as the majority of Dublin’s poor must live in.

When at last the common-sense of the people of Dublin reasserts itself, and men and women begin to protest against this suicidal destruction of the Irish race in a war that is not of their making, and for an Empire that they abhor, the cheap wits of the recruiters sneeringly tell them that there is more danger of death in a Dublin slum than in a trench in the line of battle

But you can die honourably in a Dublin slum. If you die of fever, or even of want, because you preferred to face fever and want, rather than sell your soul to the enemies of your class and country, such death is an honourable death, a thousand times more honourable than if you won a V.C. committing murder at the bidding of your country’s enemies.

These are war times. In times of war the value of the individual life is but little, but the estimate set upon honour is even higher than in times of peace. True, the conception of honour is often all wrong, but the community and the individual in time of war do esteem highly the individual who sets his own conception of honour higher than his regard for his own life.

The boy or man who has a soul strong enough to resist all blandishments to betray the cause of freedom as he sees it, who is strong enough in his own mind and purpose to face the prospect of long unemployment and its consequent misery and want, who can see day by day his strength wasting and his body shrinking for want of nourishment, who knows that that nourishment will be his for a time if he is prepared to sell himself into the service of the age-long enemy, and who in face of all this is yet man enough to hold out to the last, should he die in his Dublin slum is nevertheless a hero and a martyr fit to be ranked with and honoured alongside of the greatest heroes and noblest martyrs this island has produced.

“The trenches healthier than the slums of Dublin.” Ay, my masters, but death in a slum may be the noblest of all deaths if it is the death of a man who preferred to die rather than dirty his soul by accepting the gold of England, and death in the trenches fighting for the Empire is that kind of death spoken of by the poet who lashes with his scorn the recreant who

“doubly dying shall go down

To the vile dust from which he sprung,

Unwept, unhonoured, and unsung.”

Tens of thousands of deluded Irishmen, fighting for the British Empire, perished in the trench warfare of the First World War.

In the times of the wars at the end of the eighteenth century when all that was best in Ireland eagerly, passionately awaited the coming of the French, the armies of England were at least two-thirds composed of Irishmen. Are these poor deluded fools remembered or honoured today?

Where in all Ireland could a popular demonstration be organised in their honour. Not in any one part of Ireland would any body of Irish men or women spontaneously turn out to do tribute to their memory. Nor yet could all the gold of the British Empire induce any popular body or trade union in nationalist Ireland to walk in a procession to pay the tribute of respect to their record.

But in the same period there were men and women in Ireland who with all the wealth, power, and influence of the country against them, took their stand on the side of England’s enemies, and held by that faith to the last, despite poverty, hunger and want, despite imprisonment, torture and exile, despite death by the bullet, the bayonet and the hangman.

These men and women held to the creed that England has no right in Ireland, never had any right in Ireland, never can have any right in Ireland, and so holding they believed that whilst England so holds Ireland – whilst England is here at all – every enemy whose blows hurt England is a natural ally to Ireland, every blow which weakens England, loosens a link of the chain that binds Ireland in slavery.

These men and women, who were they? In what estimation are they held in Ireland today? They are the heroes and the heroines of the popular mind – the demigods of modern Irish history. Scarcely more than a century is gone and already they are enshrined in the memories of the Irish race, whilst all who fought for England are forgotten, or repudiated when remembered.

Did you ever hear an Irish man or woman say, “my grandfather fought for England in ’98 ?” and expect to get popular approval or respect because of that fact? You did not. But if ever you met a man or woman who could say that their grandfather or great grandfather, fought against England in ’98, were you not proud to meet them, and did not you and all your friends look upon them with respect because of what their ancestor had done against England? You did. And you were quite right, too.

Who are they who in press and on platform pour their praises on the heroism of our poor brothers whom they have driven or coaxed to the front?

But some people in Ireland do honour the men who fought for England in ’98, or pretend to honour them. Who are these people? They are the people whose ancestors were the greatest enemies of the Irish race, the evictors, the floggers the pitchcappers, the exterminators of the Irish people.

The descendants of the landlords who “enforced their rights with a rod of iron and renounced their duties with a front of brass.” And some people there are who pretend to honour the men who fight for England in our day.

Who are they who in press and on platform pour their praises on the heroism of our poor brothers whom they have driven or coaxed to the front?

Who are they? Why, they are the men who locked us out in 1913, the men who solemnly swore that they would starve three-fourths of the workers of Dublin in order to compel them to give up their civil rights – the right to organise.

The recruiters in Dublin and in Ireland generally are the men who pledged themselves together in an unholy alliance to smash trade unionism, by bringing hunger, destitution and misery in fiercest guise into the homes of Dublin’s poor.

On every recruiting platform in Dublin you will see the faces of the men who in 1913-14 met together day by day to tell of their plans to murder our women and children by starvation, and are now appealing to the men of those women and children to fight in order to save the precious skins of the gangs that conspired to starve and outrage them.

Who are the recruiters in Dublin? Who is it that sits on every recruiting committee, that spouts for recruits from every recruiting platform?

Who are they? They are the men who set the police upon the unarmed people in O’Connell Street, who filled the jails with our young working class girls, who batoned and imprisoned hundreds of Dublin workers, who racked and pillaged the poor rooms of the poorest of our class, who plied policemen with drink, suborned and hired perjurers to give false evidence, murdered John Byrne and James Nolan and Alice Brady, and in the midst of a Dublin reeking with horror and reeling with suffering and pain publicly gloated over our misery and exulted in their power to get ‘three square meals per day’ for their own overfed stomachs.

These are the recruiters. Every Irish man or boy who joins at their call gives these carrion a fresh victory over the Dublin working class – over the working class of all Ireland.

The trenches safer than the Dublin slums! We may yet see the day that the trenches will be safer for these gentry than any part of Dublin.