The Connolly Archive - 'A New Labour Policy'

This month’s addition to the Connolly Archive is ‘A New Labour Policy’, a short piece first published in the ‘Worker’s Republic’ in January 1910. After seven years in the USA, Connolly returned home to Ireland in 1910. In this piece, written shortly after his homecoming, Connolly announces that the printing and publishing of The Harp newspaper is to be transferred to Dublin.

Connolly takes the opportunity to push the idea of one big union to take the fight to the bosses more effectively. After laying out the array of benefits that are there to win, Connolly goes on to argue for a new campaign to protect jobs and conditions in Ireland from the threats posed by the globalisation of the economy.

THE CONNOLLY ARCHIVE - A NEW LABOUR POLICY

The Harp

January, 1910

With this issue of The Harp we begin a new edition – and a new epoch of our existence. For the past two years this journal has been printed and published in America as the official journal of the Irish Socialist Federation of the United States. Many circumstances – chief among them being the cheering news of the reorganisation of the forces of Socialism in Ireland on a basis wide enough for all the activities of all its adherents – have induced us to transfer the office of publication to Dublin.

Socialism in Ireland needs a representative in the press devoted to its cause, and unhampered by any other affiliation. That representative we propose to be. It shall be our aim to place our columns and our poor abilities at the service of all the brave and unselfish men and women who are battling for social righteousness against the forces of iniquity which control and poison human life today.

We shall not demand that the man or woman whose hand or voice is raised in protest or rebellion against tyranny must be at one with us upon the means to be taken to build the new social order; let us but agree that the social order must be built anew to serve the ends of righteousness, and built upon a recognition of our common heirship and ownership, and, we believe, the incidents of the struggle against the common enemy will, in itself, force the necessary tactics upon the mind of all.

Therefore we can wait, and we ask those socialists who differ from us in our conception of what the tactics of the army of revolution should be, to wait also. Let us have patience with one another; let us remember the truth that Irishmen are ever ready to forget, viz., that we must tolerate one another or else be compelled to tolerate the common enemy. This does not mean that we have altered or abandoned, or propose to alter or abandon, our belief in the correctness of the principles for which we stood in Ireland from 1896 onward.

We still believe that those principles contain the salvation of Ireland, socially and nationally, we still believe that the struggle of Ireland for freedom is a part of the worldwide upward movement of the toilers of the earth, and we still believe that the emancipation of the working class carries within it the end of all tyranny - national, political and social.

But we have come to the opinion that in the struggle for freedom the theoretical clearness of a few socialists is not as important as the aroused class instincts and consciousness of the mass of the workers. Therefore we are willing to work and cooperate heartily with any one who will aid us in arousing the slumbering giant of labour to a knowledge of its rights and duties.

Whilst we are as firm as ever in our belief that the only hope for Ireland, as for the rest of the world, lies in a revolutionary reconstruction of society, and that the working class is the only one historically fitted for that great achievement, we are prepared to cooperate with all who will help forward the industrial and political organisation of labour, even should the aim they set for such organisation be far less ambitious than our own. We invite the cooperation of all who will work with us toward that end.

The Harp shall be a free platform from which every friend of freedom can voice his aspirations without fear, favour or affection; this paper will not muzzle its readers, and will not allow itself to be muzzled. We scorn the puny weapons in the intellectual armoury of the capitalist enemy, and we shall welcome the criticisms of our friends.

In conclusion then, let us state the work that, in our opinion, lies before the socialists of Ireland as the more immediately pressing, after the inculcation of the principles of socialism. That work is the proper organisation of the working class of Ireland as a coherent whole, under one direction and in one organisation.

That the workers of Ireland be organised on the industrial field not as plumbers, painters, bricklayers, dock labourers, printers, agricultural labourers, carters, shoemakers, etc., but that all these various unions be encouraged to become sub-divisions of one great whole whose aim it should be to perfect an organisation in which the interests of all should be the interests of each - in which the right of membership should rest not in proficiency at a craft or trade, but in the fact of being a member of the working class.

Such a welding together of all the forces of organised labour in Ireland would make it possible to effect a settlement of most, if not all, of the questions which today are the stock-in-trade of every quack reformer and politician, as indeed they have also been for fifty years and more.

A militant organisation of the working class of Ireland, in town and country, would have as dominant and controlling an effect upon the fortunes of the Irish working class as the Land League had upon the fortunes of the Irish farmer.

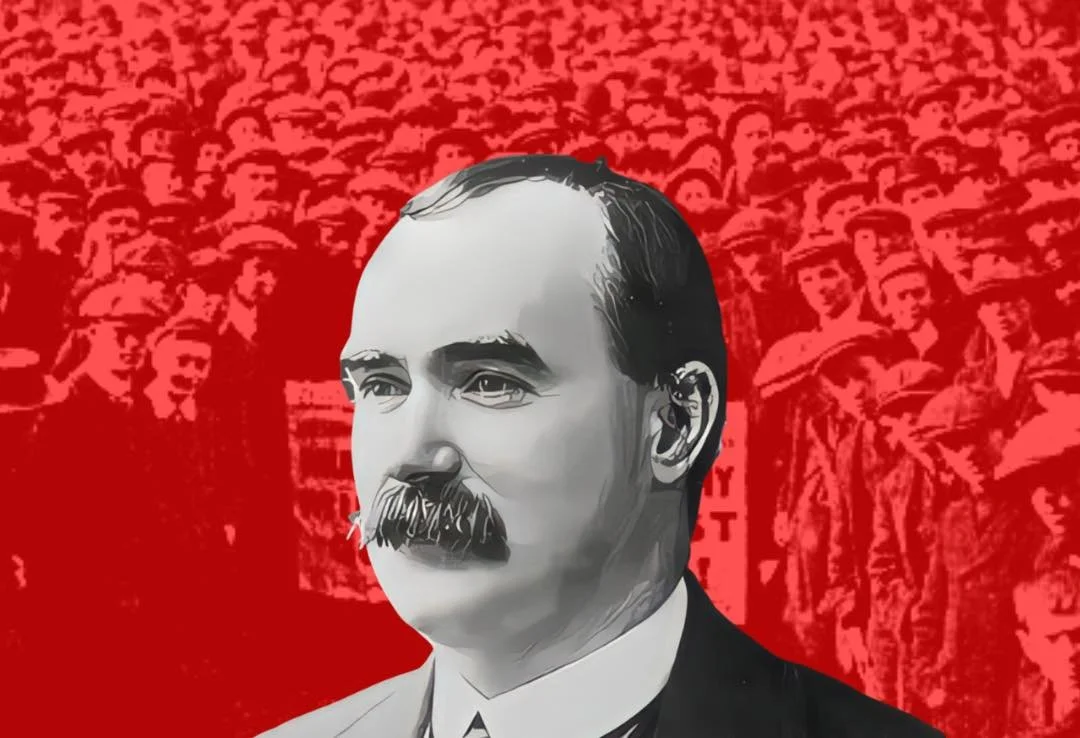

An awoken Dublin working class in 1913

It would enable labour to dictate terms to the employing class, to raise wages and to give greater possibilities of life and happiness to all, to shorten hours and to give the parent more time to spend in the bosom of his family, and give the working boy and girl more time to self-improvement and study.

It would create a force which could at any time settle the question of supporting Irish manufacture by refusing to handle all goods whose use or sale in Ireland tended to deprive Irish men and women of a chance to earn their living in their own country, and it would tend to create in the Irish working class the spirit of self-reliance which comes from grappling with problems affecting a whole class, as distinguished from the sectional selfish spirit which is bred by our present system of independent trade unions.

It would do more. The feeling of power, the consciousness of strength which would follow upon this unification of the forces of labour, would develop in our working class an ambition to do and dare greater things, to march forward to the achievement of their emancipation.

The spectacle of the whole force of organised labour in Ireland acting as a unit in the enforcement of any demand made by any of the unions in the organisation would make in the least thoughtful a newer, brighter, more hopeful conception of human relations than is to be found in the ranks of any unions which accept the capitalist idea of individualism.

Capitalism teaches the people the moral conceptions of cannibalism – the strong devouring the weak; its theory of the world of men and women is that of a glorified pig-trough where the biggest swine gets the most swill. The idea of human relations which would grow out of the working class of Ireland solidifying and concentrating their forces for their common benefit – and their abandonment of the idea behind the English system of trade unions which has hitherto cramped and dwarfed their mind and powers would make for human brotherhood and a conception of the universe worthy of a really civilised people.

It shall be our purpose in The Harp to work for such a reorganisation of the forces of organised labour in Ireland – the organisation of all who work for wages into one body of national dimensions and scope, under one executive head, elected by the vote of all the unions, and directing the power of such unions in united efforts in any needed direction.

At present we shall do no more than suggest the idea to the trade unionists of Ireland, reserving a fuller outline of the principles of organisation involved until a future date. It is to be hoped that those who are to-day loyally working for the benefit of organised labour, under the hampering conditions of old style trade unionism, will seriously consider the great advantages which this new style would give to their organisations, and bring the subject of a national organisation of labour in Ireland up for discussion in their unions.

And let them remember that the system of organisation we suggest is that which has enabled the Industrial Workers of the World in America (the I.W.W.) to defeat the Steel Trust, the most powerful Trust in the world – to defeat it in the very hour of its victory over the old style trade unions; it has enabled the French Confederation of Labour to win last year eighty-three per cent of its strikes; and it gave victory to the agricultural labourers of Parma, Italy, despite all the military power of the Government which aided the landlords and used the military as scabs in the harvest field.

One other question we propose to drop here as a seed in the minds of the toilers of Ireland, to germinate and fructify until the time comes to harvest it. It is this; We have often heard our fellowworkers in the ranks of organised labour in Ireland complain about City Councils, Poor Law Guardians, Rural and Urban Councils, Catholic and Protestant Churches, Railroads, Dock and Harbour Boards, and other public bodies, as well as private capitalists, importing into Ireland articles which could be produced as well in Ireland, and the production of which on Irish soil would keep at home many thousands who are now compelled to flee to the moral abyss of American or British cities. Now, suppose you had a national organisation of Irish workers controlling all the building and transport trades, as well as the others, and suppose the executive of this union were issuing an order to its members to refuse to handle transport, or work beside anyone engaged in handling or transporting such imported articles, and suppose the toilers of Ireland responded to such a call – as the farmers of Ireland had responded to similar calls in the Land League days – how long do you suppose such importation would continue?

Some socialists will accuse us of being chauvinistic. We are not. But we believe that the toilers of each country should control the industries of their country and they cannot do so if these industries have their location for manufacturing purposes in another country.

Therefore, after long and mature deliberation upon the matter in all its aspects we affirm it as our belief that the working class of Ireland should prevent, by united action, the conquest of the Irish market by any capitalist or merchant whose factories or workshops are not manned by members of their organisation.