Book Review - The 1981 Irish Hunger Strike: An Account from Declassified British Documents, By Michael C. Mentel

The story of the 1981 hunger strike has been told in numerous books, with Ten Men Dead, Nor Meekly Serve My Time and Richard O’Rawe’s Blanketmen and Afterlives giving particularly valuable insights. But one aspect to the hunger strike which has not received the attention it deserves is the British government’s perspective.

This book, published this year by McFarland & Co, starts to fill that gap. Mentel, an American solicitor who enjoyed a distinguished career in his field, studied British government papers released into the public domain, with his research culminating in a book that reveals much about the internal discussions of Margaret Thatcher’s government.

The book is broadly divided into three sections – a potted history of Irish nationalism, the H-Block struggle and hunger strikes, and their later significance.

However, the account of Irish nationalism provided is confusing. There are some clear errors – Charles Stewart Parnell, for example, was not imprisoned for two years. Added to this, the Fenians are conspicuous by their absence, with the IRB ‘apparently’ coming to the fore from the mid-1880s on. The description of the Tan War given is also baffling. The narrative Mentel presents as prologue to the events of 1981 obscures more than it illuminates.

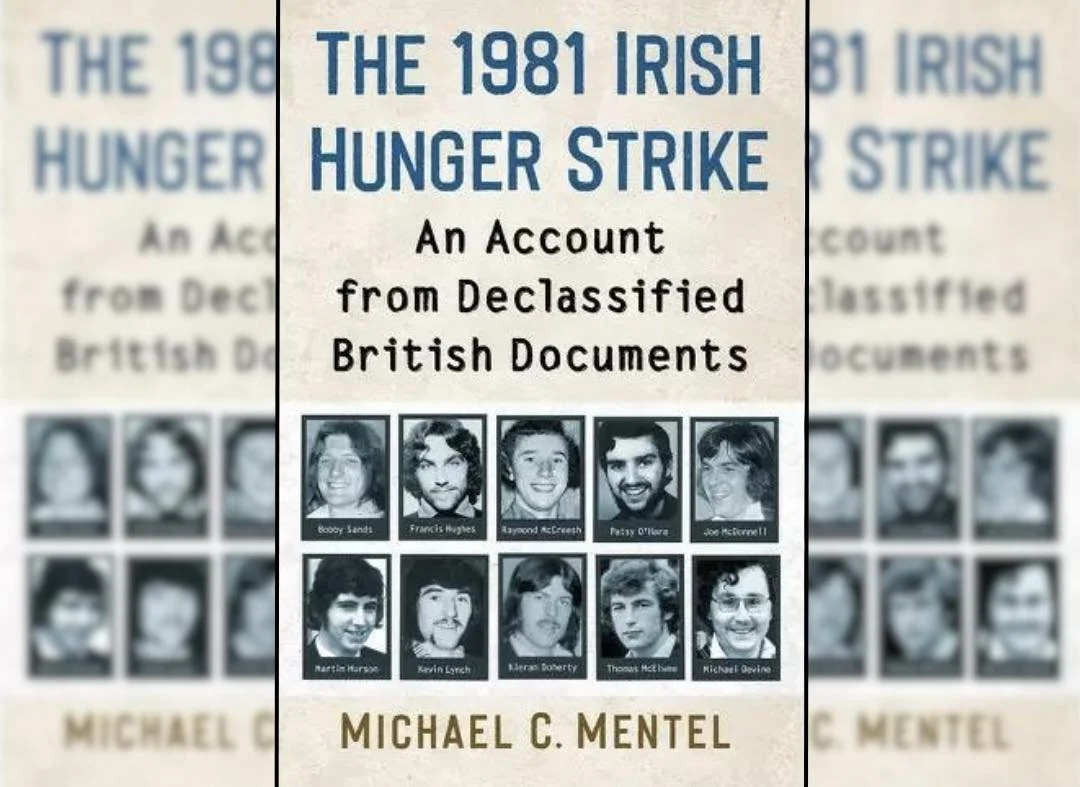

The cover of the book.

Things improve somewhat when Mentel turns to the prison struggle of the 1970s. However, if one did not know Mentel was a solicitor it becomes apparent from his style.

The narrative of the hunger strike is founded on his extensive research of British government papers which he cleverly deploys. Despite this, the book suffers from the omission of some sources – Nor Meekly Serve My Time, Gerry Adams’ Before the Dawn and O’Rawe’s works are not referred to once. The absence of these sources, and more, weakens Mentel’s overall analysis.

Ed Moloney’s Secret History of the IRA is another notable omission, particularly in the light of Mentel’s view that the channels opened between the IRA and British government in 1981 played a significant role in paving the way for the Good Friday Agreement.

The 1981 Hunger Strike reads like a first draft rather than the finished product. Mentel’s style is very lawyerly; a major contention of his is that Thatcher’s government was intransigent and misrepresented the prisoners’ position more subtly among themselves and explicitly to political and Catholic figures, as well as to the families of the hunger strikers. This is a good point, but every time it can be made it is - repetition does not improve it.

There are a number of factual errors - for instance, the IRA Army Council consisted of seven members, not eight - and numerous typos, some more serious than others as when we are told Bobby Sands received 30,092 votes rather than 30,492.

The range of errors and typos is disappointing and speaks to a rushed production. This is a great pity as despite the aforementioned shortcomings, Mentel’s book is well worth reading and offers an important glimpse into how the 1981 hunger strikes and its repercussions was seen within Whitehall.