The Bilingual Signage Bogeyman

Due to its visibility in the public sphere, signage has long been a focus of Irish language activists. Equally, for opponents of the language, the mere thought of seeing Irish on street signs, road signs, and on public buildings, has been a bogeyman. In reality, these opponents view minority language rights as a threat to the hegemony of English.

Going back to the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, the early years of the language revival, the British colonial regime were enthusiastic in attempting to stamp out the visibility of Irish in the public sphere. In 1905, Niall Mac Giolla Bhríde from Dún Fionnachaidh, Co. Dhún na nGall, was fined by a colonial policeman for displaying Irish on the cart he used for his business.

Pádraig Pearse and Conradh na Gaeilge subsequently took up the case in an effort to help Mac Giolla Bhríde, with Pearse acting as his barrister pro bono. Ever since then, questions over signage and place names have been recognised by language activists as a key battleground to raise the status of the Irish language in the public imagination.

In the Twenty-Six Counties in the twentieth-century, English only road signs were defaced by language activists. In Gaeltacht areas, and in the areas surrounding them, signage continues to be a problem as local authorities often disregard legislation.

In the Six Counties, the hostility of unionism presents a barrier to the visibility of Irish on street signs. In council areas where reactionary unionist politicians dominate, their restrictive policies make it impossible for Irish to be given equal recognition on street signs.

Bilingual council signs vandalised by reactionary unionists.

Moreover, even in council areas where equality on signage is the norm, unionists often deface the Irish language text on the signs in the dead of night. Between 2017 and 2022 bilingual signs were vandalised over three hundred times, costing councils nearly £40,000 to repair.

In recent years, the efforts of language activists in the Six Counties, including in An Dream Dearg and Conradh na Gaeilge, have been successful in getting favourable bilingual signage policies introduced in a number of council areas. For example, it will now be easier to have equal status given to Irish in the Belfast City Council area.

The requirement that only 15% of residents on a given street need to vote in favour of introducing bilingual signage serves to make it far more likely that bilingual signage will be erected and the rights of the Irish speaking minority respected in these areas.

Predictably, many unionists are apoplectic at the thought of Irish being visible in the public sphere, but it doesn’t just stop there - the existence of the Irish language itself is the thing that really bothers these reactionaries.

And it is during periods where the language makes an advance that we can always expect a local Seoínín to rear their head. In this instance, it was none other than journalist Malachi O’Doherty, who, obviously irked at receiving a ballot to vote on bilingual signage in his neighbourhood, took to the famously non-divisive Belfast Telegraph to decry the signage as ‘divisive’.

The original ‘opinion piece’ by journalist Malachi O’Doherty.

O’Doherty deployed a familiar pattern when it comes to such West-British opinion pieces:

A) Pretend you are actually in favour of the Irish language, when clearly you oppose it. According to O’Doherty it ‘wouldn’t bother him’ if every street sign in ‘Northern Ireland’ was bilingual. Yet, he goes on to pen an article against the notion of bilingual signage, knowing full-well that within the sectarian Six County statelet it would be impossible to introduce such signage in unionist dominated areas.

B) Make ludicrous claims like ‘people won’t be able to find their way around’ with bilingual signage. This surely must come as a shock to the millions of people living in the Twenty-Six Counties, Wales, Catalonia etc.

C) Ignore the fact you are in Ireland and deploy a strawman argument around your own sense of smug cosmopolitanism. In this instance, O’Doherty asserted that he has ‘lodged an application with the city council to have English and French dual signage for my street’. But as Mr O’Doherty knows full-well, we are not in France.

D) Finally, and most importantly, say it is the ‘fault of political campaigners’ for ‘politicising the language’ and making it ‘divisive’, despite surely being aware of the centuries of political acts and social policy imposed by British colonialism and the Six County statelet upon Irish speakers which politicised the language in the first place.

Later that same week, O’Doherty opined that ‘I think we can safely assume that compulsory Irish in schools will be dropped in a united Ireland’. But despite the noise made by such colonised individuals, amplified by the large media platforms they pontificate from, the Irish language continues to make advances in the public realm in the Six Counties, thanks to the determination of the activists there.

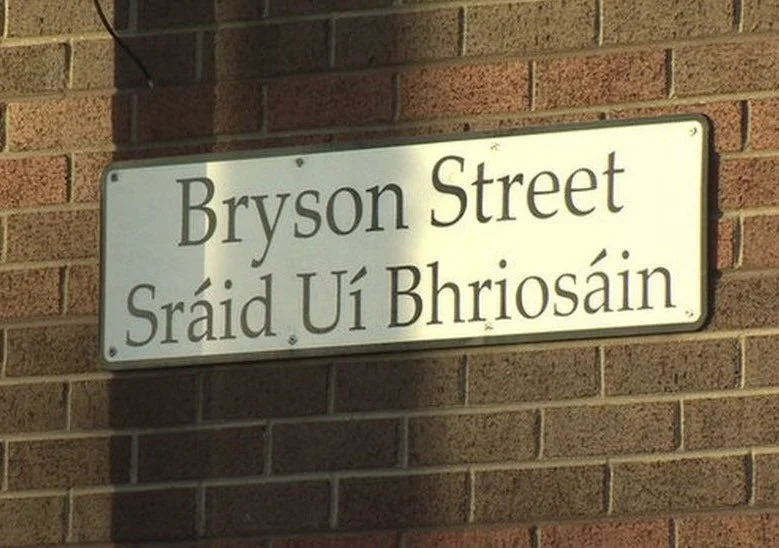

A bilingual street sign on Sráid Uí Bhriosáin in East Belfast.

In the Twenty-Six Counties, bilingual signage is no longer a contested issue, except when sections of the business class of the Gaeltacht determine that ‘tourists will get lost’ if monolingual Irish language signage is applied to towns like Daingean Uí Chúis.

However, an equally important issue is continued use of Anglicised place names in the Twenty-Six Counties by society in general. In Wales - a state still under control by London - moves have been made to decolonise the names of national parks, giving them their proper Welsh titles.

Yet, over one-hundred-years since being able to control policy around language and culture, the Twenty-Six County government have made no similar moves, preferring instead to talk up ‘Ireland’ as a monolingual bastion of the Anglo sphere in order to appeal to multinational companies.

In the New Republic that we want to help build, a determined effort would be made to decolonise our public sphere and place names - restoring An Ghaeilge to its rightfully prominent place in Irish society.