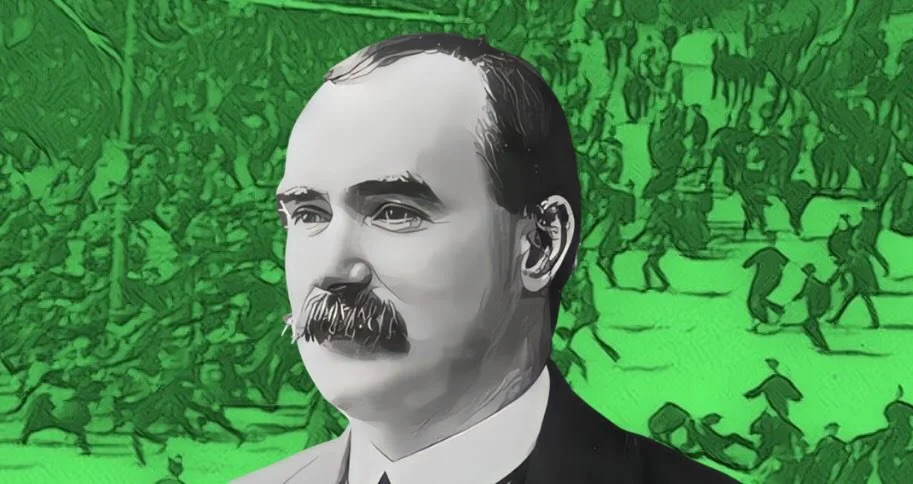

The Connolly Archive - 'The Dublin Lock-Out And It’s Sequel'

This months addition to The Connolly Archive series is ‘The Great Lock-Out and Its Sequel’, which was first published by James Connolly in The Workers’ Republic on the 29th May 1915.

In this piece, Connolly pays tribute to James Nolan, John Byrne and Alice Brady, three trade unionists who were killed during The Great Lock-Out of 1913.

Connolly then looks at the outcome of the struggle a year on from when it ended, utilising the example of a recent increase in wages won by organised Dublin dockers who had remained loyal to each other and their union.

In contrast to this, those dockers who rejected or abandoned the union failed to win a similar wage increase. Alone and isolated from their collectively organised fellow workers, they were now at the mercy of their employers to decide their worth in shillings and pence.

Locked-out workers and their families waiting on food relief to land on the docks in 1913

The Dublin Lock-Out and its Sequel

First published in ‘The Workers’ Republic’, 29th May 1915

Do you wish proof of the value of organisation to the workers, or proof of how impossible it is to destroy organisation if its members are loyal! I can give you that proof from the records of our own union.

Let me give you a little bit of history – history of very recent date. You remember the great lockout in Dublin in 1913-14; you remember how the Dublin employers smarting under the defeats inflicted upon their individual efforts to keep their workers in slavery, at last resolved to combine in one gigantic effort to restore the irresponsible reign of the slave drivers such as existed in Dublin before the advent of the Irish Transport and General Workers’ Union.

You will remember how four hundred employers banded themselves together to destroy us, and pledged their sacred word of honour that they would wipe that union off the map; that when the fight was over no man or woman affiliated to us, or friendly to us, would ever be employed in Dublin.

You also remember how they did more than pledge their honour – the honour of some of them would not fetch much as a pledge – but they also deposited each a sum of money in proportion to the number of employees each normally employed, and that money deposited in the Bank in the name of their association was to be forfeited, if the depositor came to terms with the union before his fellows.

Thus strung together in bonds of gold and self-interest, you might think they were well equipped for beating a lot of poor workingmen and women with no weapons but their hands, and no resources but their willingness to suffer for the right. But they were taking no chances. They laid their plans with the wisdom of the serpent, and the unscrupulousness of the father of all evil.

Before the lock-out was declared they went to the British Government in Ireland, to its heads in Dublin Castle, and they said to that Government, “now, look here, we are going to make war upon the Irish Transport and General Workers’ Union, but we believe that we cannot succeed as we should wish, while peaceful picketing is allowed.

We know it is allowed in England, in Scotland, and in Wales, but we don’t want it allowed in Ireland.” And the Government said: “all right, gentlemen, the law allowing peaceful picketing is only a scrap of paper; we will tear it up while the fight is on.”

The employers said again: “good, but these Labour men and women will hold together while they are able to hold public meetings, and hear their speakers encouraging them. Could His Majesty’s Government not manage to suppress public meetings, whilst the fight is on?”

And the Government answered: “Suppress public meetings, why, of course: the law which permits public meetings in Ireland is just another scrap of paper, and has been torn up many a time, and oft; we will tear it up again, so as to help you in the good work of crushing the Labour movement.”

And you know, the British Government kept its promise to the employers. All through that long and bitter struggle, the elementary rights won by Trade Unionists by a century of sacrifices were denied to us in Dublin, although freely exercised at the same time in England.

, James Nolan, was killed during the Lock-Out by a drunken Dublin Metropolitan Police mob on Eden Quay

The locked-out worker who attempted to speak to a scab in order to persuade him or her not to betray the class they belonged to, was mercilessly set upon by uniformed bullies, and hauled off to prison, until the prison was full to overflowing with helpless members of our class.

Women and young girls by the score, good, virtuous, beautiful Irish girls and women were clubbed and insulted, and thrown into prison by policemen and magistrates, not one of whom were fit to clean the shoes of the least of these, our sisters.

Our right of public meeting was ruthlessly suppressed in the streets of our city, the whole press of the country was shamelessly engaged in poisoning the minds of the people against us, every scoundrel who chose was armed to shoot and murder the workers who stood by their Union.

The wife and daughter of Dublin labourer, John Byrne who died after a DMP baton assault on Burgh Quay

Two men, James Nolan and John Byrne, were clubbed to death in the street; one, Byrne of Kingstown, suffered unnameable torture in the police cell, and died immediately upon release, one young girl, Alice Brady, while walking quietly homewards with her strike allowance of food, was shot by a scab with a revolver placed in his hands by an employer, and within twenty-four hours after the murder, that scab was walking the streets of Dublin a free man.

Our murdered sister lies cold today in her grave in Glasnevin – as true a martyr for freedom as any who ever died in Ireland. But she did not die in vain, and none who die for freedom ever die in vain.

16-year-old factory worker, Alice Brady, was shot by an armed scab on Mark Street

Well, did the unholy conspiracy against Labour achieve its object? Was the union crushed? Did our flag come down?

Let me tell you our position today, and tell it by an illustration.

We recently put in a demand for an increase of wages in Dublin, for all classes of labour in our union. That demand was eventually met by the employers, and at a Conference between the representatives of the Union and the Employers were prepared to settle matters through the Union, and that whatever terms were then agreed upon would determine the rates for the quays and elsewhere, wherever our men were employed.

Here are a few of the advances thus agreed upon, as well as the advances arranged with other firms not represented at the Conference, but dealing directly with the Union Officials.

Stevedores Association: One penny per ton increase on all tonnage rules.

Deep Sea Boats: One shilling per day on all day wage men.

Casual Cross Channel Boats: One shilling per day.

Constant Cross Channel Boats: Eightpence per day.

Dublin and General Company’s employees: Four shillings.

Dublin dockyard labourers: Three shillings per week.

Ross and Walpole: Two shillings per week.

General carriers’ men: Two shillings per week granted direct to men after receipt of letter from the Union.

These comprise the larger firms, many smaller firms also made advances as a result of action of the Union, and in every case the advance made was in proportion to the manner in which the men had stuck to their Union.

The firms whose employees had fallen away gave poor increases or none at all; the firms whose members had remained loyal to the Union, paid greater increases, and so the men reaped the fruits of their loyalty, whilst those who were faint of heart were punished by the employers for lack of faith in their Union and their class. So it shall ever be.