On The Shoulders Of Giants . . . 'Larkin's Scathing Indictment Of Dublin Sweaters'

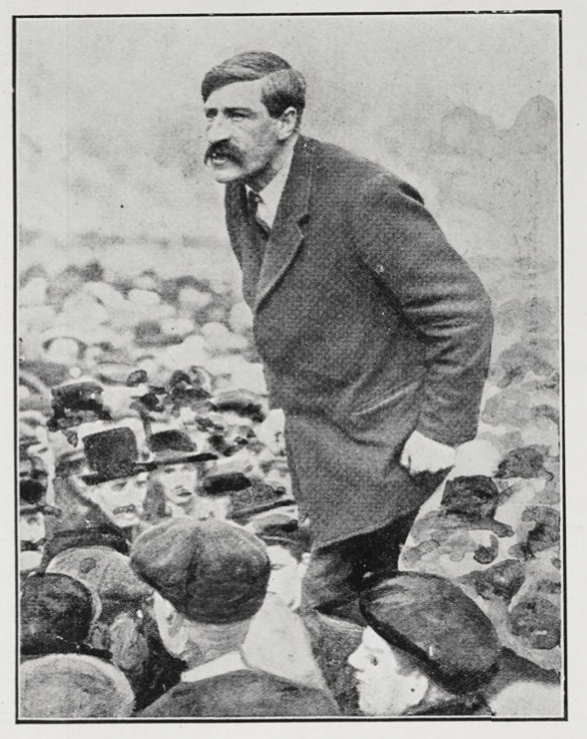

This month, as part of our On the Shoulders of Giants series, and on the anniversary of Jim Larkin’s death in 1947, we republish the transcript of a long two and a half hour long speech delivered by Larkin to the Dublin Castle Commission. The commission was set up October 1913 to investigate the circumstances that lead to what became known as The Great Lock-Out.

William Martin Murphy, in opening for the Employers Union, asked the Commissioners to allow his union to be represented by Counsel, as they did not have the ability to present their own case. Larkin, on behalf of the trade unionists, said that while they had no objection, they were surprised that these so-called invincible captains of industry, as the employers so often claimed to be, were so deficient in mental and oratorical ability as to be unable to put forward their own case.

Their appeal proved the workers’ contention that they (the workers) carried on industry, and the employers had given away their whole case, and so the employer-led lock-out was unjustified. The Commissioners agreed to allow Counsel, led by T.M. Healy, the future Governor General of the counter revolutionary Irish Free State, to represent the employers and asked the workers’ representatives, James Connolly amongst them, did they desire assistance. Their reply was “No; we know our case.”

Larkin rose to deliver his speech directly after counsel representing the Employers Union gave their case.

* This transcript was written by a reporter working for the establishment press. It is not a complete transcript of everything Larkin said, but is the only one available.

Jim Larkin was a skilled working-class orator, able to connect with, organise and stir workers to fight for a better future.

Larkin’s Scathing Indictment of Dublin Sweaters

The Irish Worker

October 1913

LARKIN'S SCATHING INDICTMENT OF

THE DUBLIN CAPITALISTS.

At the inquiry of the Industrial Commissioners into the Labour conditions in connection with the Transport Workers’ dispute at Dublin, the following speech was made by Mr. James Larkin on Saturday, October 4, 1913, in summing up the case on behalf of the workers: —

Mr. Larkin, addressing the Court, said: —

I hope the Court will bear with me during the short time now at my disposal while I put before it a reply, somewhat of a personal character, but which, at the same time, will cover the matters dealt with during the past few days.

The first point I wish to make is that the employers in this city, and throughout Ireland generally, think they have a right to deal with their own as they please, and to use and exploit the workers as they please. They assume all the rights and deny any to the men who make their wealth. They are men who say they are of paramount intelligence; they say they are able in organising abilities as “captains of industry;” that they can always carry out their business in their own way.

They deny the right of the men and women who work for them to combine and try and assist one another to improve their conditions of life. While denying the men and women who work for them the right to combine, these men not only take unto themselves this right, but they also intimidate the men—a matter upon which I shall enlarge later on.

EMPLOYERS HAVE FAILED.

The employers have failed everywhere. They claim to have the fullest capacity for carrying on industry, and as they stand between the consumer and producer they also claim the right to control production. But we deny that.

We say they are not fitted to carry on industry. Business in this city and country is carried on in a chaotic manner. There is no system. This want of system we want to prove and will prove by the appearance of the men themselves in the witness- box.

The employers were invited to meet the representatives of the working classes, men denied access to education and the assistance it might have been to them. Their claim is that as they have the means they have the right to do as they like with their employees. The working classes deny the right of the masters to lock out their employees. The masters violate all laws, even the laws of Nature. The employers have shown their incapacity during the inquiry.

These astute gentlemen, who claimed to have a capacity for organising and conducting business, and most of whom had had a public school education, these men have had to employ lawyers to explain their case to the Court for them. They have had to call upon the Irish Bar for three of the most brilliant men who ever spoke or worked at that Bar—and yet these men, able men, eloquent, have made a most unholy hash of the whole business.

The employers have proved the case for the workers. They have demonstrated individually and collectively that they cannot carry on business properly. The employers claim that they have the law on their side, but their counsel, Mr. Healy, says there is no law in Ireland, and I agree with him.

The masters assert their right to combine. I claim that the same right should be given to the workers. There should be equal rights for both sides in the contest. The employers claim that there should be rights only on one side. The employers are the dominant power in this country and they are going to dominate our lives. As Shakespeare says, “The man who holds the means whereby I live holds and controls my life.” That is not the correct quotation, but I want to put the matter in my own way.

CAPTAINS OF INDUSTRY.

For fifty years the employers have controlled the lives of the workers. Now, when the workers are trying to get some amelioration, the employers deny the right of their men to combine.

Man cannot live without intercourse with his fellow beings. Man is, as has been said by an eminent authority, a social animal. But these men—these “captains of industry ”—draw a circle round themselves and say, “ No one must touch me.” But they have no right to a monopoly.

The workers desire that the picture should be drawn fairly. But these able gentlemen who have painted the picture for the employers have found that they could not do it. They have got the technique, the craftsmanship, but they have not got the soul. No man can paint a picture without seeing the subject for himself. I will try to assist our friends who have failed. As I say, they have the pigments and the craftsmanship, but they have not been able to paint a picture of life in the industrial world of Ireland.

21,000 FAMILIES LIVE IN SINGLE ROOMS.

Let us take the statement made by their own apologist. Let us take the statement by Sir Charles Cameron. There are, he says, 21,000 families, averaging 5 to each family, living in single rooms in this city. Will these gentlemen opposite accept responsibility?

They say they have the right to control the means by which the workers live. They must, therefore, accept responsibility for the conditions under which the workers exist. Twenty-one thousand families living in the dirty slums of Dublin, five persons in each room, with, as admitted, less than 500 cubic feet of space. Yet it was laid down that each adult should at least have 300 cubic feet space.

In Mountjoy Gaol—where I have had the honour to reside on more than one occasion—criminals (but I am inclined to believe that most of the criminals were outside and innocent men inside) were allowed 400 cubic feet. Yet men who slave and work, and their women—those beautiful women we have among the working classes—are compelled to live, many of them, five in a room, with less than 300 cubic feet.

They are taken from their mother’s breasts at an early age, and are used up as material is used up in a fire. These are some of the conditions that obtain in this Catholic city of Dublin, the most church-going city, I believe, in the world.

HUMAN CLAIMS.

The workers are determined that this state of affairs must cease. Christ will not be crucified any longer in Dublin by these men. I, and those who think with me, want to show the employers that the workers will have to get the same opportunities of enjoying a civilised life as they themselves have.

Mr. Waldron, the Chairman of the Canal Company, on the previous day admitted that right. There is one phase in the present condition of affairs which I will not put before a mixed audience such as this, but of which you are all aware.

One of the chief arguments used against Larkin is that he came from Liverpool, but I claim to have as much right to speak in Dublin as Mr. Healy, although I do not come from Bantry. But wherever I come from it is time that someone came from somewhere to teach the employers Christianity. Will the gentlemen on the other side show me that they have a right to speak in the name of the Irish people?

The majority of the employers in Dublin have no associations by birth with Ireland: they have no interest in Dublin; they have come here simply to grind wealth out of the bodies and souls of the workers, their wives and their children.

My claim to speak is a human claim, a universal claim, one not limited by geographical boundaries. Mr. Healy has drawn a picture from the employers’ view-point. I want to show the other side, the true side. I will use other pigments and more vivid colours.

Go to some of the factories in Dublin. See some of the maimed men, maimed girls, with hands cut off, consumptive, eyes punctured, bodies and souls seared, and think of the time when they are no longer useful to come up to the 2s. 6d. to £1 a week or other standard. Then they are thrown on to the human scrap-heap.

MASS OF DEGRADATION.

See at every street corner the mass of degradation controlled by the employers, and due to the existing system. Their only thought was the public house, and, driven to death, they made their way thither to poison their bodies and get a false stimulant to enable them, for a time, to give something more back to the employer for the few paltry shillings thrown at them.

These are the men whom the employers call loafers. Mr. Murphy has agreed with me that in the main the Dublin worker is a good, decent chap; but Mr. Murphy and others of his class deny the Dublin men the right to work on the Dublin trams, on the Dublin quays, and in the Dublin factories. They deny Dublin men the right to enjoy the full fruit of their activities.

Why? Because they want to bring up in their place poor, uncultured serfs from the country, who knew nothing of Dublin or city life—to bring these men into a congested area, so that they would bring down the wages of the men already here. The employers do this because their souls are steeped in grime and actuated only by the hope of profit-making, and because they have no social conscience.

But this lock-out will arouse a social conscience in Dublin and in Ireland generally. I am out to help to arouse that social conscience and to lift up and better the lot of those who are sweated and exploited. But I am also out to save the employers from themselves, to save them from degradation and damnation.

WHAT IS ANARCHY?

Take Mr. Murphy. I do not mean in any personal sense. I know that Mr. Murphy is imbued with strong views of the rights of property, and on the right to use workers as he pleases. Mr. Murphy is one of the strongest men in the capitalist class of this country, in the Kingdom, on the Continent, or even in America. But the day of the capitalist class is rapidly passing.

Mr. Murphy believes in Trade Unionism, but he must make his own Trade Union. Mr. Murphy says that Larkin’s Union is not a Trade Union, but is Anarchy. But what is Anarchy ? Anarchy means the highest form of love. It means that a man must trust his brother and live in himself. We cannot do that yet. We are all set out to injure one another.

The present system and policy of those opposed to us is to pull down, but our Anarchism means universal brotherhood. Mr. Murphy, though he is one of the ablest exponents of capitalism, admitted that he did not know the details of his own business, and claimed that I had no right to interfere with it.

HUMAN THOUGHT.

Confronted by a wage slave, he was absolutely unable to state his own case. He admitted he had no knowledge of the facts put before him of the details of his own business. He said he had had no strikes of any moment during his connection with industrial concerns, but I have proved that his life has been one continuous struggle against the working classes. I give him credit that in a great many cases he came out on top.

Why? Because he has never been faced by men who were able to deal with him, because he has never been faced by a social conscience such as has now been aroused, and according to which the working classes could combine to alter the present conditions of Labour.

He had said he would drive “ Larkinism ” headlong into the sea—I evidently have the honour of coining a new word. But there is such a thing as human thought—and nobody has killed it yet, or driven it into the sea, or kept it from making progress.

A very able theologian of the Church with which I have the honour to have some association said to me: “That a wall should be built around Ireland so high that the thought of modern Europe could not get over it.” But nobody can build such a wall or kill human thought, not even the theologians, the police, or the politicians—corrupt as they are.

Mr. Murphy ought to realise in the later hours of his life, and before he passes hence, that he ought to give something back to the men who made his wealth for him and raised him to the plane of the capitalist, that they deserved something to encourage them to rise from the lower plane on which they existed to a higher plane on which they might live.

We have seen the multifarious operations of Mr. Murphy all over the world. He is an able man, with the power and capacity to buy up the ablest men of the working classes, and he has used his power relentlessly. He may use that power for a while, but the time must come when such power would be smashed, and deservedly smashed. There must be a break.

Mr. Murphy said his workmen got certain wages, but I deny that statement. If Mr. Murphy could prove his statements as to the wages of tramwaymen I would call the men together in the morning and send them back to work to sign any document Mr. Murphy might submit. There are not ten men in the tramway service driving cars who ever got 31s. per week. The wages start at 24s. 6d., and only a limited number would ever get to the standard of 30s.

There are creatures who were once men. If you are a creature you get promotion ; if you are a man you are victimised, degraded, and driven out. Such a system of despotism would not be tolerated in any other country in the world for an hour. The Star Chamber of Charles has been succeeded by the Star Chamber of William the First of Dublin. The man who does not bring charges against his fellow-man has no business in the tramway company. An inspector who does not give in a complaint within a given period loses his job.

MR. MURPHY AND DUBLIN CASTLE

It was a matter of public knowledge some time ago in the case of the police, that a man in the service was of no use unless he brought 5 charges within a certain period, and it is the same thing in the Tramway Company. Mr. Murphy had denied that he had any agreement with the authorities in Dublin Castle, but I can prove Mr. Murphy had direct communication. One man who is on the cars at the present moment has done nine months for wife beating, yet the tram company’s regulations say that no man with a bad character could enter the company s employment.

Surely a man who got nine months imprisonment for beating his wife is a man with a bad character, and one that should not have got a licence for driving a car. He got the licence from the Hackney Carriage Commission of Dublin. That Commission is controlled by the police, and Mr. Murphy has the son of a police officer in the tramway office. Another man, an ex-policeman, who ruined a young girl down in Irish town, is driving a car on the Sandymount or Donnybrook. line. How was it that the police authorities granted a licence to him ?

With the exception of such hirelings, and men introduced by John Dillon Nugent, no man could be got to work the trams. Nugent induced certain men to desert Larkin under the charge that he and his friends were attacking the Catholic Church.

MONOPOLY OF PUBLIC UTILITY.

Every means, police, Government, the influence of the church, has been used to induce men to betray their own class and to act as hirelings. If that is the system that Mr. Murphy wants to carry on, I say let him do it. Mr. Murphy has said he is quite satisfied with the way his cars are worked. So are my friends and I.

Mr. Murphy has got a system of extorting wealth from the public of Dublin without giving a fair return for the money. He charges for a mile and a-half in Dublin as much as is paid for a three-mile journey in Belfast—bad as Belfast is. He has a monopoly in a matter of public utility, and imposes prohibitory prices which he could not impose if the concern was one under public control. The Corporation of Dublin have given him privileges which they themselves should possess.

Mr. Larkin went on to read the rules under which men were employed by the Tramway Company. Any man might have a complaint made against him. He might make his statement and prove that he was right, but still he was mulcted, and there was no appeal.

He repeated that there were no men now in the tramway service except a few organised scabs. They were working cars, and it was only through pure good luck that they were working them without killing people; they were taken on without any teaching, and got licences without having the right to claim them. A “ spare ” man might work for two years without getting one penny, and the average paid to the “ spare ” man was 14s. a week.

That was the reason they brought men from the country—poor, unfortunate fellows who were induced to break their family ties to come to Dublin and accept conditions laid down by a brutalised manager. But every human being in Dublin said that the system must stop; public conscience had been expressed upon the conditions under which the tramwaymen worked. Every good man and every good woman had condemned the whole attitude of the employers in the matter.

Dealing with the drivers on the tramway cars, he said they were compelled to stand on the platforms for hours without food. They had a power brake, but they were obliged to use it only with heavy cars on the Dalkey line in case of danger. If they used it in Dublin they got into serious trouble. A driver had to use only a hand-brake that was put together by handymen, and half the staff on the tramways consisted of handymen.

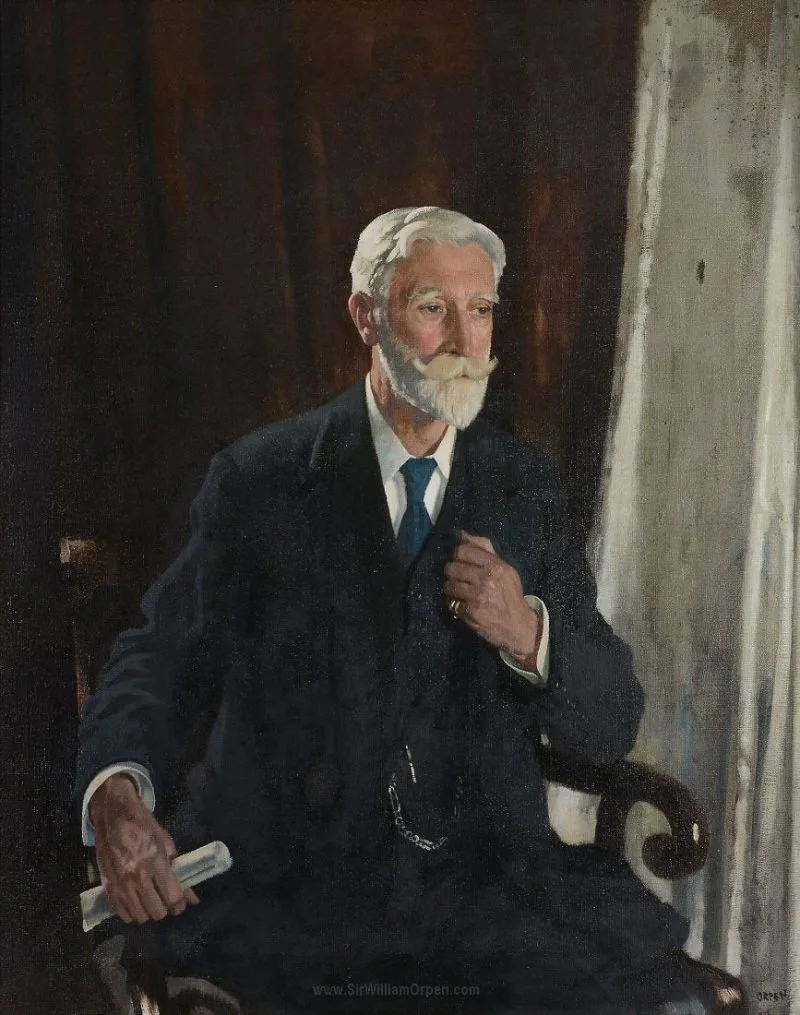

William Martin Murphy was an outspoken anti-trade union employer who owned many businesses and media outlets across Dublin and beyond. He was determined to smash trade unionism in Ireland.

COWARDLY POLITICIANS.

In Belfast the conditions of service were nearly 30 per cent, better than in Dublin. There the men had the right of appeal before a Board or Committee if a complaint was made by any official. The difficulty in Ireland was that the English, Scotch and Welsh employers were educated to a higher standard than the Irish employers, and that was why they recognised combinations of workmen who came to discuss ways and means with them.

“ According to some of the gentlemen opposite, there were no strikes or lock-outs in Ireland,” Mr. Larkin proceeded, “ and they also tell us that since Larkin came to Dublin there have been more strikes than there were in the whole industrial life of Dublin. But there was no industrial life in this country up to comparatively recently, because, unfortunately, the Irish workers had been trusting to other people to do their work.”

Proceeding to deal with the case of the West Clare railway men, Mr. Larkin said that on that line the most brutal despotism was carried on. Mr. Murphy had tried to disassociate himself from it—a degree of despotism never known in any other Christian country. No protest was made by the Press of Ireland.

What conditions were the unfortunate men living under ? Twelve bob a week, working all day and into the night. Some milesmen got ten or eleven bob a week, and they were living in hovels in West Clare—the place where they shot landlords for the farmers years ago.

In West Clare the men thought they ought to have something better, and they paid their own railway fares and came up to Dublin to make an appeal, but they were scouted and told to get back again. And when they went back—incensed at the feeling that they were not going to be met by the employers—they came out on strike.

The Nationalist local Press, controlled by the politicians, deliberately obscured the issue; and in every column of every paper it was seated that an English Union was interfering with and destroying an Irish industry. Those men were left at the mercy of the capitalist class, backed up by their agents and apologists. The priest went into the cottage and told one man to blackleg it—to go back to work and not be foolish, and one or two of them went back. Some of the men were driven out of the country, some to the workhouse, and some to the asylum—and this in the twentieth century! The member for West Clare sat mute in Dublin and in the House of Commons, the same as the cowardly politicians are sitting mute now throughout this country, and who daren't face the men they’re supposed to speak for. They destroyed these men’s homes and broke their women’s hearts, and for what reason?

As Mr. Murphy said, this was a lesson that would teach the Dublin tram-men not to go out on strike. I say here that if an Irish Union, with the same capacity as the Railway Union, had been controlling the Great Southern Railway strike, I know what the result would have been. They would never have beaten the men.

AGITATORS MUST BE WIPED OUT.

The priest was appealed to; the politician was appealed to; the members of the Irish Party were appealed to; but the result of all was that there was to be no assistance for the men; and the Board of Trade was appealed to to send some one from England, and they refused to do so.

Thus the men were left at the mercy of the capitalist classes, who were backed up by other agencies. They were told not to mind their fellow-men, but to go into work and blackleg upon them. In that way one or two broke away. The County Council met, and, controlled by gentlemen of the type of Mr. P. J. O’Neill, said these men were agitators —they must be wiped out and destroyed. They were thus thrown on the roadside, driven out of the country, to the workhouse, the asylum, or to the broad fields of the Western Continent. They were dealt with as no human beings were ever dealt with before.

INTIMIDATION.

Turning again to the Tramway question. Mr. Larkin referred to the meeting of men addressed in the Antient Concert Rooms by Murphy before the strike took place.

The cleverest methods, he said, were employed in convening that meeting. Mr. Murphy got his unfortunate dupes into the hall. For any capitalist or clever man to go to his unfortunate dupes, said Mr. Larkin, and get them into a hall and pay them a day’s wages and give them drink and food to take part in a packed assembly to sign away their rights—these men were brought down in cars, and two hundred policemen were lined up, and every man had to go inside the hall, and if he did not he was a marked man, and he was sacked on the following day.

And they say there was no intimidation—here Mr. Larkin produced a rough baton from a parcel, and showing it to the Court, said: There is no intimidation in Ireland. No! But every man in a particular company before the lock-out was supplied with one of these, and afterwards each man got a gun, but the cowardly hounds were afraid to use them. And these are the men who talk of intimidation by labour leaders!

This man, Murphy, compelled the police to monopolise the streets, to bring the men into the hall under duress to sign away their liberty, and then his fellow-conspirator, Mooney, threw odium on Larkin. Is there a man amongst them from Kerry to Belfast who could meet me on an open platform and argue his case? If there is let him come. Let them pay Mr. Healy if they like, and I’ll guarantee he won’t be governed by the laws of evidence then.

THE FACTS OF LIFE.

The reason why my friend could not paint the picture is that he does not know the picture. He has been so immersed in law books that he does not know anything of the facts of life. Some of the men who attended Mr. Murphy’s meeting were hirelings paid to cheer, and one poor drunken fool was brought on the platform to denounce Larkin. He had been suspended during the day, but because he denounced Larkin he was brought back to his car.

Murphy told the people of Dublin that this fellow, Larkin, does not amount to anything, and he said there will be no strike. But on the Tuesday morning of Horse Show Week he found that there was a strike, and only for John Dillon Nugent, of the A.O.H. (Board of Erin), his company would be at a standstill, as he says himself—it is at a standstill now for that matter. Now, in the field of battle (proceeded Mr.. Larkin) the man who betrayed his comrades is shot like a dog; and the day will come when a blackleg in the industrial warfare will be recognised as a traitor.

HIRELINGS OF ULSTER.

Discussing the fund for tramwaymen who did not strike, he said it had been got up and subscribed to by men of the classes who had always been the curse of Ireland, who had bred disunion and dissension, and who had sucked the life blood out of the country. These were the people who had been sending subscriptions of pounds, ten shillings, etc., to what they called loyal men—the class, both Protestant and Catholic— who had tried for their own reasons to depopulate and destroy the country.

Among the men controlling that fund was a member of the Privy Council of Ireland, who gave evidence the previous day. That gentleman was elected to the Privy Council to control forces in Ireland, and he should have stood aside and remained neutral ; he should have advised both sides to stop the infernal warfare and prevented men being bribed to destroy themselves.

“ There is another Privy Councillor,” said Mr. Larkin. “Tom Sinclair, of Belfast, another bloodsucker, another capitalist, who at the present moment is engaging himself with the hirelings in Ulster; and the Privy Council in Ireland are condoning and endorsing his action.” With such forces arrayed against them the time had arrived when the men should articulate through the unions they belonged to.

“ I was one of the first to advise that there should be no strikes or lock-outs in Ireland,” Mr. Larkin went on, “ and I formulated in set phrases the methods that should be used.” With regard to the 1908 Conference, he said he had absolutely nothing to do with the negotiations and never saw the agreement entered into on that occasion. He was refused admission to the meetings which had taken place in Dublin and London. “I was apologised to by Sir Anthony M'Donnell,” he added, “ for the way I was treated by the employers at that Conference. Any man that states I had any part in the 1908 negotiations in the final conclusions is stating what is a palpable untruth. There was no doubt some undertaking was given, but like the Treaty of Limerick it was broken before the ink was dry.

FREE LABOUR IS BAD LABOUR.

They came to an understanding, and I ask them to produce the document. Mr. Larkin proceeded: “Let us see whether there is anything about ‘ free ’ labour in it, about wearing of badges. I have been a Trade Unionist since I was thirteen years of age, and if any man can produce a document signed by me approving of ‘ free ’ labour, I will go down on my knees to him and apologise.

I am not in a fighting mood, but I want to be understood. I want to argue the position of my class, my abhorrence for what is called ‘ free ’ labour. I think the employers, from their own point of view, would be well advised to realise that ‘ free ’ labour is bad labour, and that it would be better for them to recognise proper associations of good workmen, and thus get the only guarantee worth considering.

And what about the men who came here and talked about the wages paid to women and then refused to answer a question? As long as the sweating and unsatisfactory employer is allowed to shelter behind the others, so long will people be allowed to bring in what they call Irish industries and sweat poor, unfortunate women.

An employer says, “ I drew up the agreement and they signed it.” If you only knew the horrors of that place; but I have no time to dwell upon it. He brought in a Frenchman and an Englishman. He came to Ireland himself, or his father did—he comes from Belfast, which is very near Ireland. He brought with him a Belfast man, and when he found this Belfast man had some sympathy with the poor workers, he “sacked” him, and brought over an Englishman. The Englishman immediately decided to reduce the wages, because he found the workers were not organised. The girls were flung on the streets, and had no one to appeal to.

They came down to Liberty Hall to the man who is trying to advise the Irish working class at the present time. But were they advised to go on strike? The man who calls people out on strike takes a great responsibility, but the man who locks out his employees has a double responsibility. I told these girls to make representations to their employer, and said I would get a City Councillor or some one to go with them. And when this man was reasoned with what did he do? He drafted an agreement, got the girls to sign it, and within two hours he was breaking it himself; he sent away one man who had been concerned in the dispute, he “ sacked ” a boy, and on Monday morning he left two girls out. Then he wanted the other girls to teach the new hands who had replaced the dismissed employees.

LABOUR CONDITIONS.

The girls stood it for three weeks until this man again brought trouble upon himself. And then he got a document from a member of a Freemason Lodge—I think it is the Duke of York Lodge—(laughter) —and I will prove that no officer of the Board of Trade, or of the Corporation has ever visited the part of the premises complained of. There is one lavatory in the place for male and female workers, and beyond that statement I will not go.

The wages paid to the workers were cut down from a low living standard until the girls could no longer submit to the tyranny. He said that two of the girls who caused the trouble earned 30s. 7d. between them. In English firms—Cadbury’s, for instance—the workers would get 9s. 6d. per cwt. instead of 4s. 2d.

The girls got a large quantity and could make weight up very quickly, but this gentleman asked them to make four small sweets out of a similar quantity of material that they had been getting for one. It would take four times as long to do the work and the man actually wanted to cut the rate. This class of men are all right when they are treating with poor, unorganised gills, but there is growing up such a state of conscience amongst the workers of this city that will change all this. His statement with reference to two girls earning 30s. 7d. for one week between them is a lie.

TENPENCE WAGES FOR TEN DAYS’ WORK.

I can produce a document issued by a Belfast firm who came down to employ Dublin Catholic girls out of sheer philanthropy—the capitalists are all philanthropists! Two of the girls employed by this firm—their father having been ill for some time—worked for the firm on material that is sold in Grafton Street at £1 an inch. What were their wages for ten days? Ten pence each! That cannot be denied. “No fines, no deductions, total paid lOd.” Fancy a girl working for ten days and only receiving lOd.!

Let us turn to Mr. Wallis, who so kindly suggested that I should become his manager. Perhaps it would be as well for his business and for the country generally if I were appointed manager for a time. Mr. Wallis has kindly admitted that when I met him I was always reasonable, but I always tried to get as much as I could without giving anything away.

Mr. Wallis at the present moment has got £600 belonging to the men locked out. Illegal deductions are made, and the men have to submit to them or get out. Duress again. The Truck Act says this is illegal, and yet it goes on. Mr. Wallis says he has to compete with men who pay a very low standard of wages. Indeed, some rates have gone down from 2s. 6d. a ton to Is. a ton, and from Is. 6d. to Is. 2d. in other cases.

Who suffers ? The workers suffer all the time. Though these men cut and carve in competition with one another, it is always the poor people who suffer; the carters’ wages have got to be cut down to allow cost of carting to come down. In the agreement they did not even allow any time for a meal-hour. We did not object, because we knew the men had no money to pay for a meal.

I could produce other documents, but the last time the police came into my office they took all they could lay their hands on. Certain employers got hold of the agreement, and using the information in it they quoted prices so low as to cut out the former contractors. That was the loyalty that existed among the employers. Mr. Wallis rightly asks me if nothing could be done with the Union to prevent unfair competition, and I agreed it was unfair.

CLERKS WAGES 14s. A WEEK.

Mr. Hewat has been very kind and fair in his statement, and practically proves what we have said. Industry in this country is in a “ system ” of chaos, and will remain so until we find a common denominator to govern the whole business. The firm was fairly decent, and was usually dragged into trouble by relations with other firms affected by disputes.

These people go into Heiton’s yard and take advantage of the fact that the firm’s employees are not on strike, and want coal supplied to them. It is wrong in law and wrong in morals for these people to do that. Mr. Spence tried to fence the Question that the employers had deliberately avowed the intention of using the weapon of starvation.

There had been a conspiracy amongst the employers, not only against members of the Union. but against all who might sustain them with supplies. Thank God they have not realised that, and we are not starved yet. With regard to Mr. Eason, he was very fair with me. He admits he sent for me. Is Mr. Eason prepared to submit his wages’ book to any people, even to his own class? If he would agree to pay competent clerks and clever dispatch men 20 per cent, less than London rates. I will be satisfied. It does not matter to him how many hours men work, and work at top speed, and very few know the weary work of handling newspapers.

What about a man with a family getting 14s. a week in Dublin where house rent is 10 per cent, more than in London, and where the cost of living is as 106 to 100? They are paying 50 per cent, less wages than in London. Is it any wonder there is unrest? Mr. Eason says it was impossible for him to stop supplying the “ Independent” and “ Herald.” Let me ask him why he tried to stop the “ Irish Worker ” or “ Clarion ” ?

GIRLS WAGES 2s. 6d. PER WEEK.

A man is the best judge of his own actions. If he thinks a thing is right he should do it, and when I think a thing is right I am going to do it. After all, character has got something to do with a man. The appearance of a man has got a great deal to do with the man. If a man is doing right he can answer “ Yea” or “Nay.”

Mr. Healy has claimed that Mr. Jacob is a Quaker. There is not a system of working in Great Britain like that carried on by Messrs. Jacob. It is a system of espionage, and in other respects it is a hateful system. The wages paid to women by this firm in 1910, when I had reason first to interfere was 2s. 6d. per week. It was by reason of that fact that I interfered.

Some of the girl workers came to me and informed me that they were forced to work under duress—I like that word—to subscribe to Mr. Jacob’s daughter’s wedding present. I replied to them, “ If you are going to subscribe do so from the heart, and not from the pocket under duress.” I did not interfere with the workers at that time because I did not think the time was ripe for interference.

But one morning I found hundreds of the men and women and girl workers on strike and the police beating them. I took them away to a hall, and I was asked by them to say a few words. I told them, then and there, that they were unwise in coming out, and while I was speaking, a message came from Mr. Jacob that he would like to see me. I had never asked for an interview. I have never forced myself on any man.

I said I would be glad to talk the matter over with Mr. Jacob, who said he was sorry that I had interfered in connection with the workers’ subscriptions to his daughter’s wedding gift. I replied that I had done so as a duty, and Mr. Jacob accepted my answer, and said I would be welcome to visit the works at any time I liked. I said I would get the workers to return to work on the understanding that the firm would deal with them in a fair spirit. Mr. Jacob agreed to pay their wages in full on the Saturday following the interview. They all returned to work. At that time there was not one of them associated with the Transport Workers’ Union. I got them to return to work—a difficult job. I may tell you, for they did not want to go back— on a promise of 2s. per week increase all round.

William Orpen’s painting of William Martin Murphy. Besides the Dublin Tramway Company, Murphy’s other possessions included Independent Newspapers, Cleary’s and The Imperial Hotel on O’Connell Street.

THE PHILANTHROPIST.

What followed and what did Mr. Jacob do? He dismissed, one by one, everyone who was connected with the strike. A man, 24 years of age, fell while he was carrying a heavy tray and sustained fearful internal injuries. He was operated on without his consent. The firm kept him on for a time on the pretence that he would get work, and they ultimately got rid of him. He was thrown out on the street, having a widowed mother depending on him, after being twelve years in the employment of the firm. And yet this man, Jacob, talks about being a philanthropist!

Another case was that of a young man, seventeen years of age, who had one of his arms reduced to pulp as a result of an accident, and he was told by this philanthropic employer that if he was not able to do the work he should have to go. Mr. Jacob has said that he pays the same wages as other employers in the same business. But surely, a philanthropist, as Mr. Jacob claims to be, should adopt a higher standard.

I assert here that the wages paid by Mr. Jacob are the lowest in Great Britain or in any other country—even in the lowest biscuit trades in Belgium—and, in addition, the conditions in Jacobs are absolutely brutal. There is a trough in the establishment in which the water is only changed once a week, and in this the girls have to bath— and they have to submit to things like that without complaint.

We have been told that they have a resting room. Yes, when the poor girls are done up with work their almost inanimate forms are carried to this resting room, and they are laid out on a bed until they have recuperated. Not a single book is allowed into the room. They lie there until they are recovered, and then they are dragged back to the oven, the machine, or the tin-shed, as the case may be. There is a lady doctor in the establishment. Well, all I have got to say is that if there are many lady doctors like Messrs. Jacob’s doctor, it is my opinion that women should not get the vote.

By reason of their miserable wages and their conditions of work these poor girls are forced to go on the streets of Dublin, to sell their souls and their bodies, to become the victims of the brutality of police and soldiers. Why, O’Connell Street is an abomination to the Irish people!

Mr. Jacob has talked about philanthropy. Why, it would be better for Dublin and Ireland if some of our industries had never been started. There are certainly two industries we could very well do without—and these are that of the lawyers and that of the politicians.

I now wish to say a word about the farmers. Mr. Robertson has stated what is absolutely untrue. It is a fact that he employs a large number of labourers, but he does not pay them the standard rate of wages. I have been told by Mr. Healy that I came to Ireland from Liverpool. Well, I will tell you why I came to Dublin. I came here because I heard Mr. Healy was going to London, and because two great men could not be lost to Ireland at the one time.

TRUE HOME RULERS.

It is thought by some that no one should be allowed to live in Ireland except, those born on Irish soil. Well, that would be a bad thing for some of those on the other side. There is no sense in such an argument as that. The Irish workmen are out to work for a living, and to get access to the means of life. They are not going to be slaves; they are not going to allow their women to be slaves of a brutal capitalistic system which has neither a soul to be saved nor a soft place to be kicked.

Owing to chronic unemployment, and to the misgovernment of the country, there is a state of things in Ireland that has no parallel anywhere. Home Rule is essential to the class to which I belong. We are born Home Rulers. We want a true Home Rule and we want the people to govern the country—not in the interests of a few individuals, who are not for the country, but in the interests of the whole of the people.

I am engaged in a holy work. Of course I cannot now get employers to see things from my point of view, but they should try to realise my work. It has been said that Larkin has been in receipt of £18 per week. Well, Larkin is worth that, but he never got it— unfortunately.

I have earned more as a white slave than I ever got from my own class. I speak of what I know. I have starved because people have denied me food. I have worked hard from an early age. I have not had the opportunities of the men opposite, but I have made the best use of my opportunities.

I have been called anti-Christ . I have been called an Atheist. Well, if I were an Atheist I would not deny it. I am a Socialist. I believe in a co-operative commonwealth, but that is far ahead in Ireland. But why should a man not be allowed to improve the condition of things as they exist.

The farmers say they have always treated the men with justice and kindness, but that is not so. I was sorry to hear Mr. Healy express the view that the cause of the labourers in the country, and the cause of the toilers in the city, should be split up. The agricultural industry and the urban industry are interdependent, and you have got to settle both problems at the one time, and if you do not attempt to settle it, then yours will be the responsibility.

The working classes will not accept the responsibility, but they will do their utmost on all occasions to get over difficulties. We cannot trust the farmers to carry out any arrangement they enter into. I have spoken about Mr. Jacob. I hope Mr. Jacob will not take what I said in a personal sense. Mr. Jacob has said that he merely wants the same conditions as his competitors in England, but we shall show him that the conditions are much better in England than they are here. The firms in England enter into direct negotiation with their employees, they treat with the workers’ unions, and the workers claim that the same conditions should operate here.

EIGHT THOUSAND CHILDREN IN WORKHOUSE BASTILES.

Mr. Healy has made reference to “ The Chocolate Soldier,” but he, apparently, does not know that the author of that piece has drawn attention to the fact that there are 8,000 children of the poor confined in Irish workhouse bastiles. Let Mr. Healy ask Shaw’s opinion of Ireland. Shaw would tell him that when he got out of Ireland he did not want to come back because of the hellish conditions of life here.

If we had a few more Shaws and a few less Healys it would be the better for Ireland. Lawyers and politicians, and the people misled by them, are the cause of all the troubles in Ireland. The workers are now getting rid of the old, slothful, drunken fellows who pose as their leaders.

The men who are responsible for the present chaotic condition of things are the men who would not pay fair wages, or give fair conditions, and the other employers, who are willing to give these things, are victimised by unscrupulous men. The employers have combined but the right of combination must be recognised on both sides.

If an employer is a member of an association, and does not pay a decent wage, he should be socially ostracised, and if the workers do not carry out an arrangement they should be dealt with by their associations. Sauce for the goose should be sauce for the gander. I have put forward that long since, but the reply is, “No, we will have nothing but a strike or a lock-out; we will have constant dislocation of trade; and we are going to beat you down to the gutter, so that there will not be a strike for twenty years. ’

Has there been a reason why there were not strikes long ago ? Is the reason not to be found in the fact that the men have been so brutally treated that they had not had the strength to raise their heads? When I came to Dublin I found that the men on the quays had been paid their wages in publichouses, and if they did not waste most of their money there they would not get work the next time. Every stevedore was getting 10 per cent, of the money taken by the publican from the worker, and the man who would not spend his money across the counter was not wanted.

Men are not allowed to go to their duties on Sunday morning. After a long day’s work they get home tired and half-drunk. No man would work under the old conditions except he was half drunk. I have tried to lift men up out of that state of degradation. No monetary benefit has accrued to me.

I have taken up the task through intense love of my class. I have given the men a stimulus, heart, and hope which they have never had before. I have made men out of drunken gaol-birds. The employers may now drive them over the precipice; they may compel them, after a long and weary struggle, to recognise the document submitted to them not to belong to the Irish Transport Workers’ Union, but it will only be for a time. The day will come when they will break their bonds, and give back blow for blow.

They may bring to their aid men like Father Hughes, of Lowtown, who went round in a motor-car and used the power of the Church against the poor to induce them to sell their bodies and souls to capitalists like Mr. Waldron. Father Hughes has got men to sign a document that they would not belong to the Union. There were men in the pulpits of all the denominations getting up and denouncing Larkinism, but can any of them say anything against me or my private life? Yet, having taken upon themselves high office and sacred calling, they denounce Larkin—said he was making £18 a week and had a mansion in Dublin, and was gulling the working men. Do they not live in mansions and enjoy life?

THE NEED FOR LARKIN.

I am told I am an Atheist. Why, it is the clergy who are making the people Atheists, making them Godless, making them brutes! The people are going to stop that, and are going to be allowed a chance of exercising their religion. Mr. Waldron, a member of the Privy Council, and an ex-M.P., would not allow his slaves to bow down to the Creator on Sundays because he wanted to make profit out of their bodies.

Mr. Waldron has admitted that his men went to bed in their boots. What else could he expect? After walking 30 miles along a canal bank, foodless, but always having the enemy, Drink, waiting for them, foul alcohol to poison and chloroform them, quarts of porter on credit! leg- tired, soul-tired, they lay down in their dirt.

I have seen 13 men in one room lying round a big coke fire, heads to feet, in an establishment owned and controlled by this Privy Councillor. That was the man talking of Christianity! That was the man sent from Stephen’s Green to ask for Home Rule for Ireland!

Is it any wonder a Larkin arose? Was there not need for a Larkin. I have proved out of the mouth of an alleged Catholic that workmen were brutalised and denied the right to worship their God on Sunday, Catholic and Protestant employers have been equally guilty in this matter.

There are conditions of the same kind in Ulster, Munster, Leinster, and Connaught—and then Ireland sent 103 men to the House of Commons, all speaking as in the Tower of Babel. But the workers speak with one voice, and will stop this damnable hypocrisy. We want neither Redmond nor Carson, neither O’Brien nor Healy. We want men of our own class to go there and tell the truth.

We want to tell Carson that he is preaching rapine, slaughter, and disorder. Yet nobody interferes with him. Why? Because the Government know it is all gas—all froth. But they know that the workers mean business and are going to unite on the field of economic activity and abolish all racial and sectarian differences. It will be a good day for Ireland when the Carsons of all classes are cleared out of the country.

Mr. Healy, with all his eloquence, could not preach what I have preached because it would not pay. The politicians dine and wine together. The workers neither dine nor wine, but they suffer and starve together. If the employers want peace they can have peace, but if they want war they will get war.